Ajith B

The NDA government is bullish about the Indian economy’s underlying strength. There is a lot of talk about India becoming a USD 5 trillion economy by 2025, leveraging its current strengths. According to the Prime Minister and his colleagues, the country is on track to become a developed nation by 2047, its centennial year of independence. They emphasize that this inclusive economic growth will enable the poorest and most deprived people to improve their circumstances.

But how close are these claims to ground reality?

The latest UN Human Development Report shows a different picture. India is ranked 134th among 193 countries in the Human Development Index (HDI).

Instead of relying solely on economic growth to assess a country’s development, HDI takes into account three key dimensions of human development: healthy life, education, and a decent standard of living.

The latest report saw India’s HDI rank rise by one position. Slight increases in life expectancy, expected years of education, and gross national income have all contributed to this. However, there is not much to be excited about, as the country’s position remains in the medium category. India lags behind its neighbors, including China, Bhutan, and Bangladesh. This does not bode well for the government’s claims about India’s spectacular progress.

HDI and inequality-adjusted HDI (IHDI)

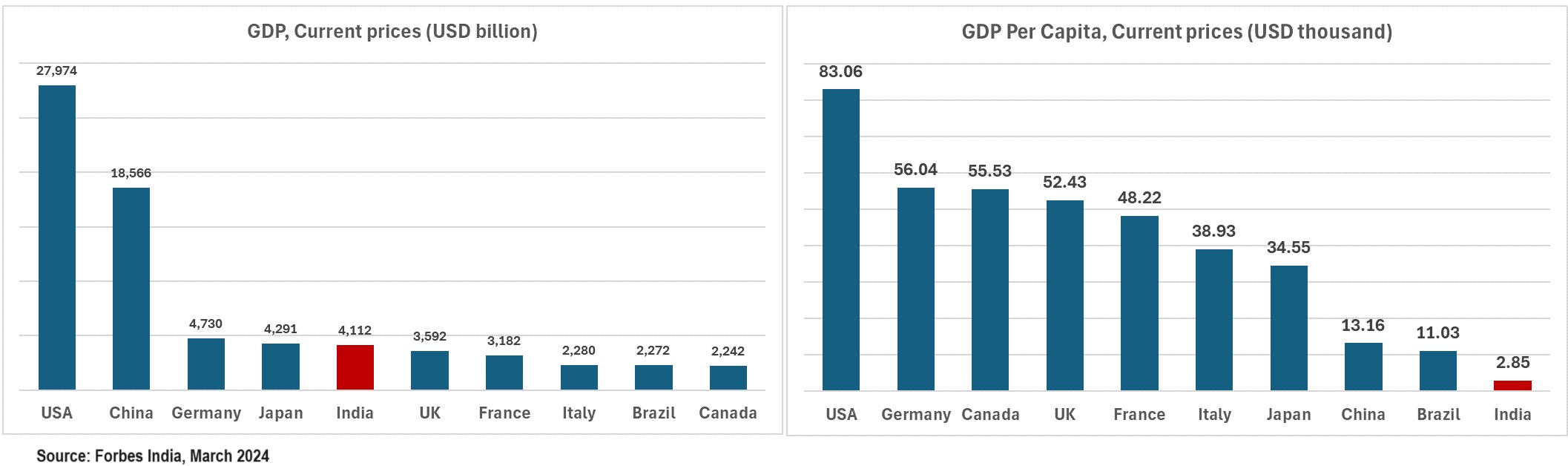

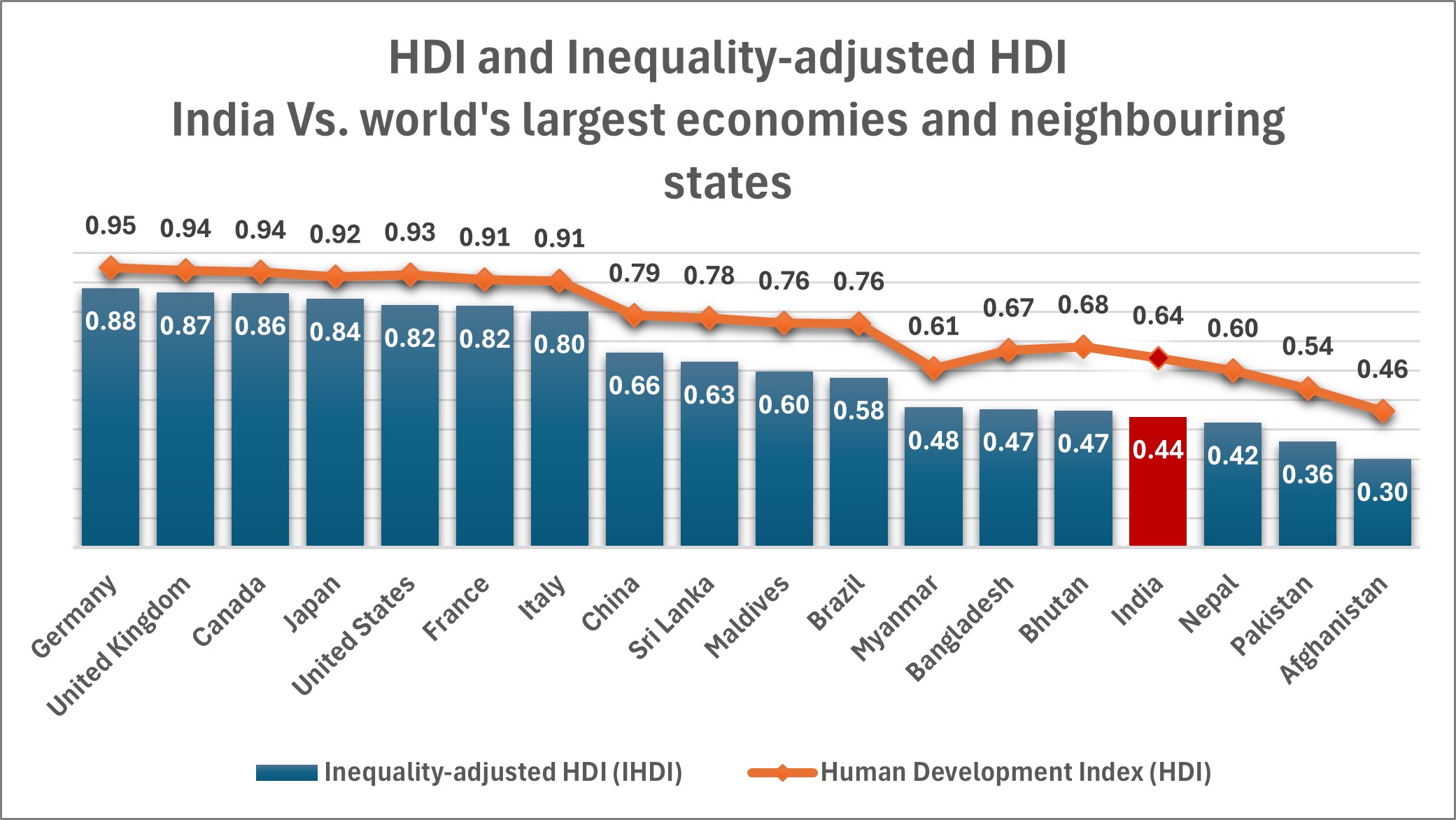

The chart below shows India’s position in HDI and inequality-adjusted HDI (IHDI) indices relative to the world’s largest economies and neighbors. The largest economies are taken for comparison because government’s claims often cite India’s GDP, which surpassed that of the United Kingdom and France in 2022 and is projected to outperform Germany by 2030.

The IHDI is a country’s human development indicator that takes into account inequality in the three HDI dimensions mentioned above.

Despite being the world’s fifth largest economy, India’s GDP per capita is low when compared to the top ten economies (see below). This is obviously reflected in its human development record.

Its standing among relatively ‘poor’ neighbors is also not to be proud of. In terms of IHDI, only three neighboring countries—Nepal, Pakistan, and Afghanistan—lag India. If we just look at HDI, Myanmar will also fall behind India.

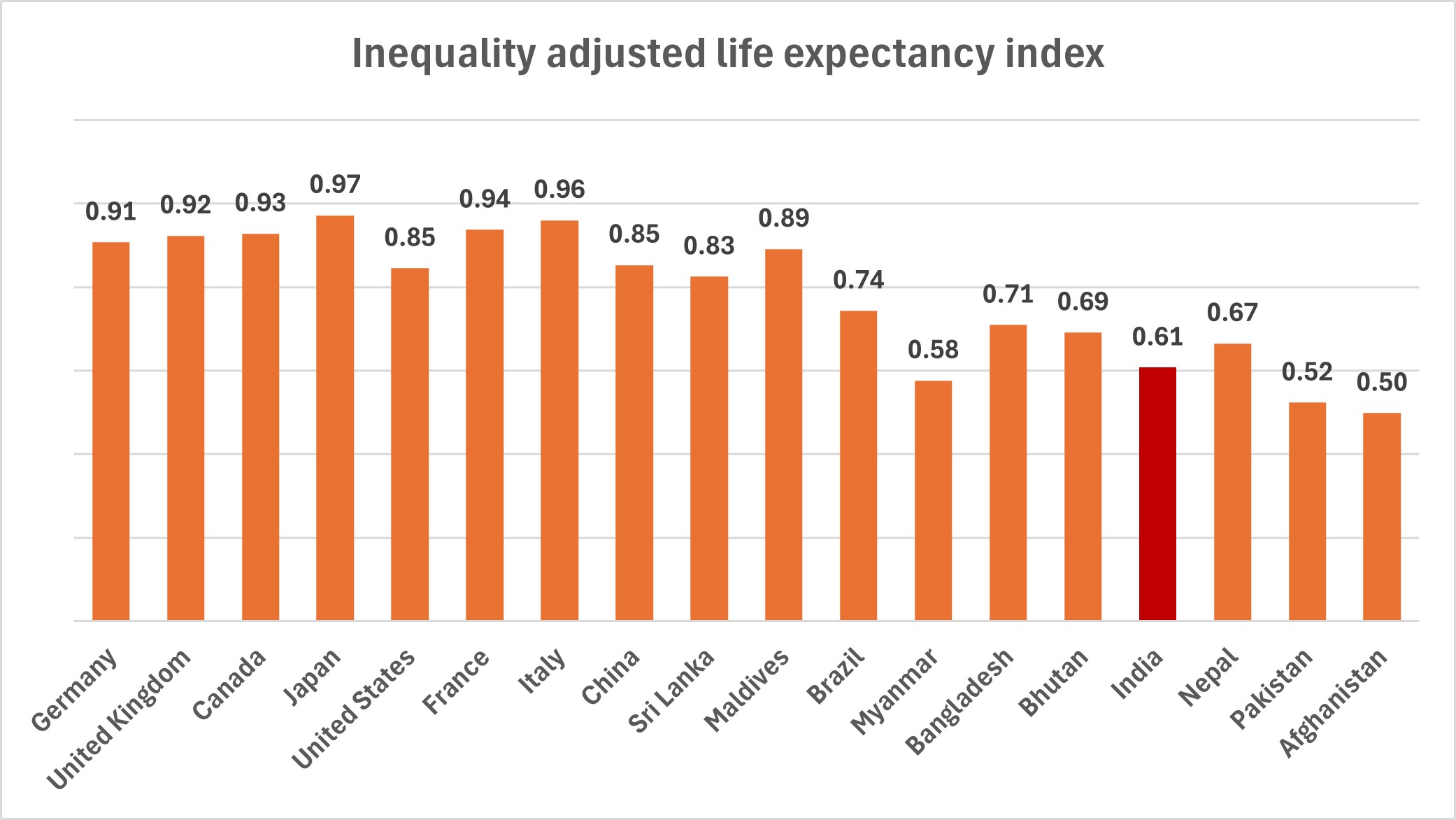

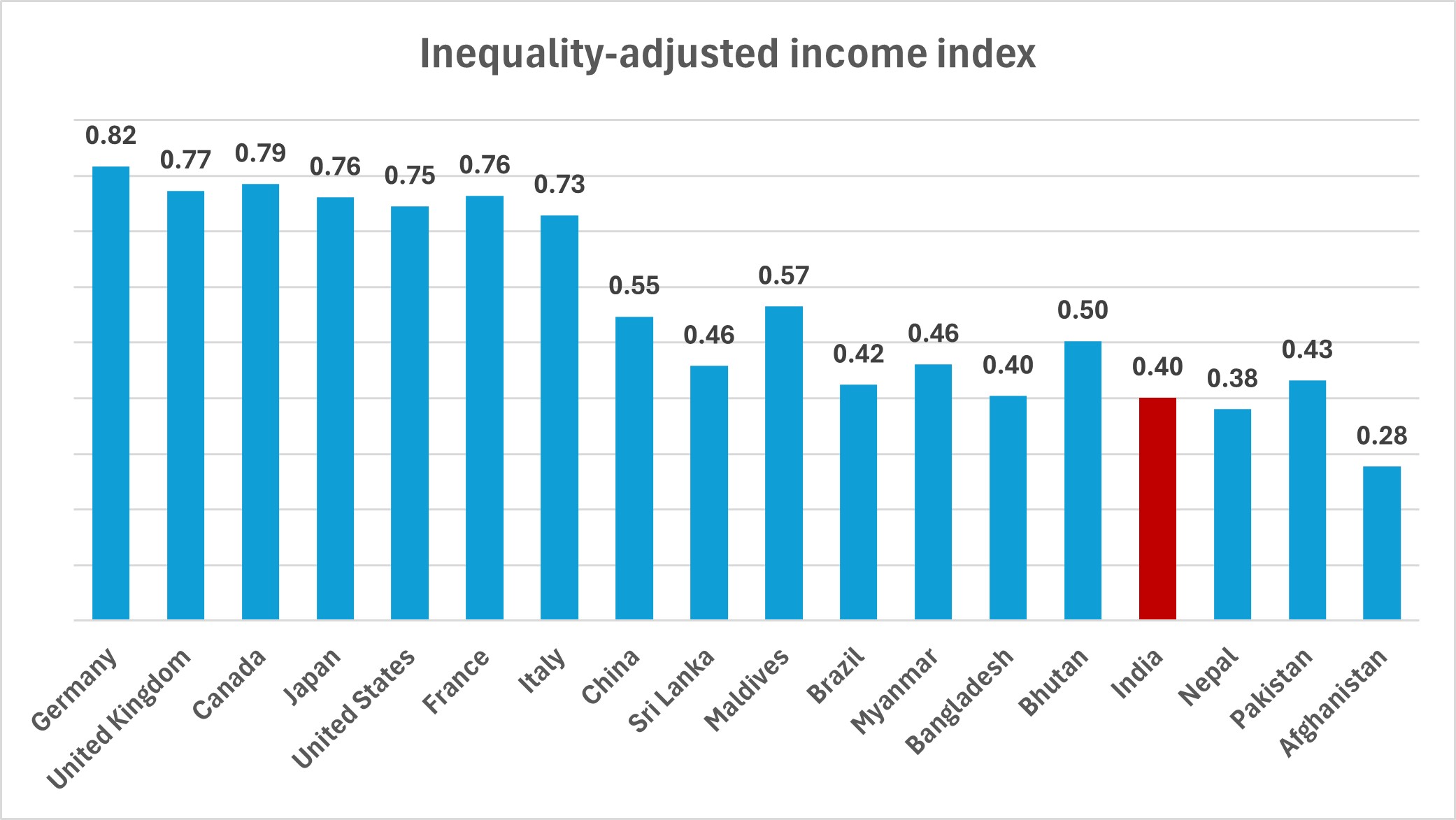

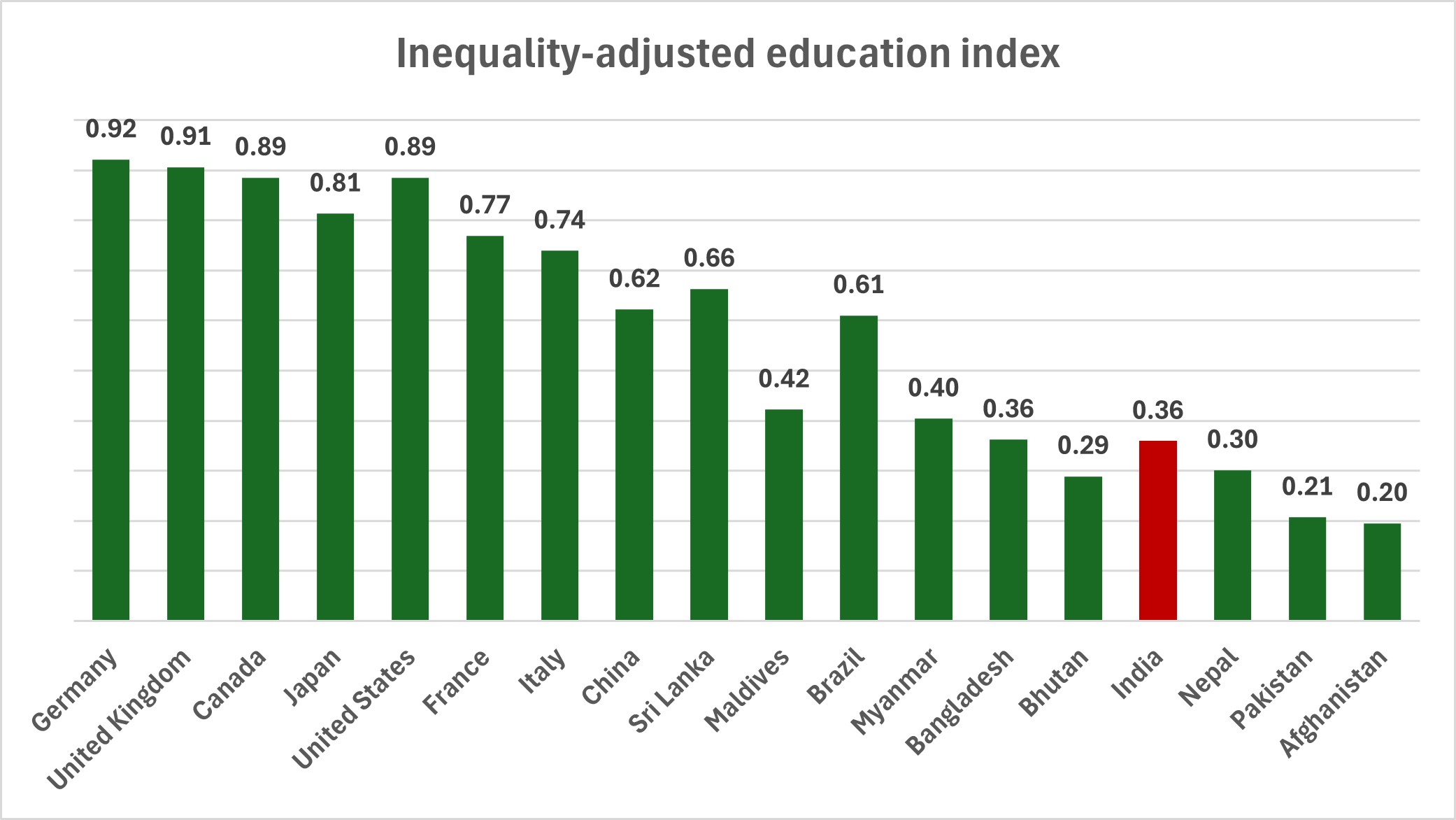

A similar trend is more or less visible in all three dimensions.

Inequality adjusted life expectancy

Myanmar, Pakistan, and Afghanistan trail India in terms of inequality-adjusted life expectancy. Life expectancy in Nepal, which lags behind India in combined IHDI, is a little better than India.

Inequality-adjusted income

Only Nepal and Afghanistan trail India among neighbours in the inequality-adjusted income index.

Inequality-adjusted education

Only Nepal, Bhutan, Pakistan, and Afghanistan have a lower inequality-adjusted life education index than India among its neighbors.

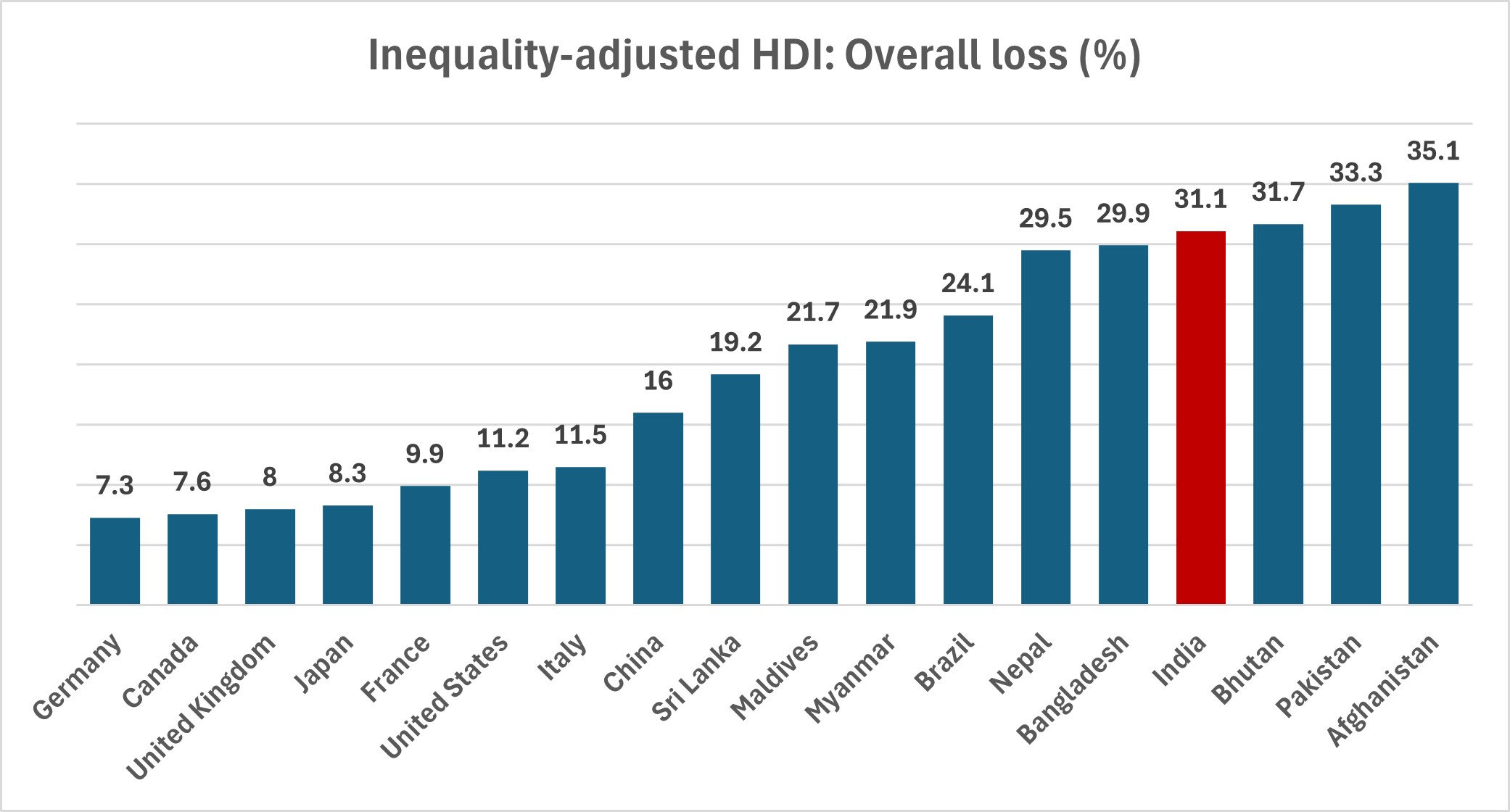

The effect of inequality

As previously stated, IHDI is calculated using HDI after accounting for the country’s inequalities in these three dimensions. If there is no inequality among people in a country, the IHDI equals the HDI. As inequality increases, IHDI falls below HDI. The chart below depicts the overall drop in IHDI due to inequality for India, as well as the world’s largest economies and neighbours.

In India, inequality has a significant impact on human development when compared to the largest economies. Its position among neighboring countries is also not enviable.

A recent paper from the World Inequality Lab provides important insights into income and wealth inequality in India. Titled “Income and Wealth Inequality in India, 1922-2023: The Rise of the Billionaire Raj,” this paper, written by Nitin Kumar Bharti, Lucas Chancel, Thomas Piketty, and Anmol Somanchi, analyzes a massive amount of data during this period and concludes that,

- Inequality fell after independence until the early 1980s, when it began to rise and has soared since the early 2000s.

- From 2014-15 to 2022-23, top-end inequality increased significantly in terms of wealth concentration.

- By 2022-23, the top 1%’s income and wealth shares are at their historical highs (22.6% and 40.1%, respectively).

- India’s top 1% income share ranks among the highest in the world, surpassing even South Africa, Brazil, and the United States.

All is not well!

(The HDI related data used in the charts is from the UNDP Human Development Report 2023-24 available at https://hdr.undp.org/content/human-development-report-2023-24 )

Ajith B is an engineer, IT expert, and social observer. He writes about technology, economics, the environment, society, and politics.