Manoj K. C.

The NDA government came to power under Mr. Narendra Modi in 2014, and they were re-elected in 2019. The key pillars of Mr. Modi’s campaign have been Achche Din (better days), Sabka Saath, Sabka Vikas (inclusive development), and Na Khaunga aur Na Khane Dunga (eliminate corruption). With electoral bonds declared unconstitutional and numerous analyses now available in the public domain demonstrating how electoral bonds were used for extortion, money laundering, and quid pro quo deals, the narrative of “Na Khaunga aur na Khane denge” has unraveled. Let us take a closer look at the first two narratives.

Achche Din

Let us look at the state of Achche Din through the following parameters: economic growth, employment status, poverty, and food security

- Economic growth

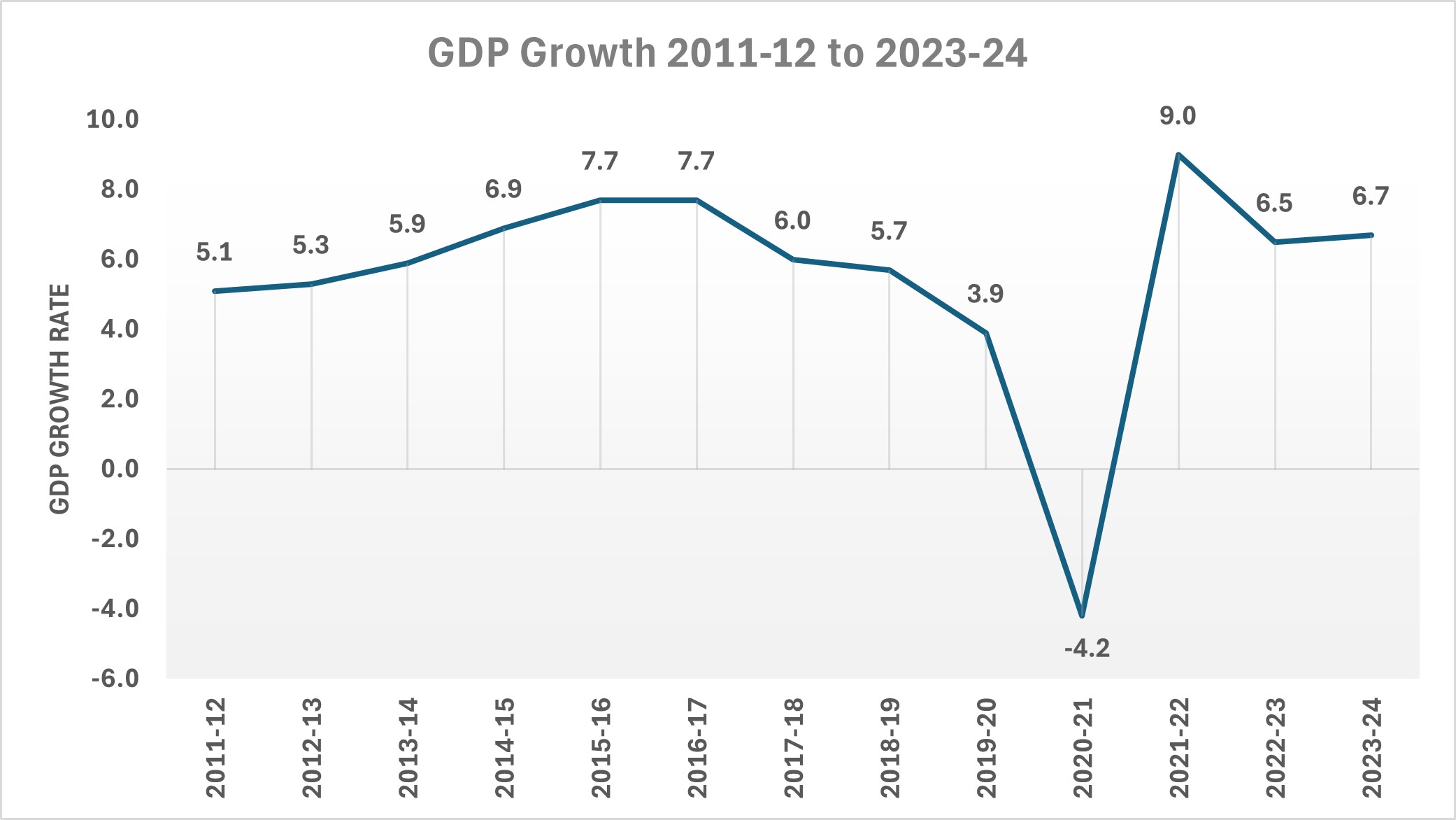

GDP growth since 2011

The government claims that GDP growth over the last ten years demonstrates the success of its economic policies, which have helped 140 crore Indians live better lives and create a Viksit Bharat.

But a closer look at economic growth since 2011, in terms of GDP, reveals another story.

Note: Figures are of gross value added (GVA) at basic prices, in constant (2011–12) prices

Key observations:

- When Narendra Modi took power in 2014, he inherited an accelerating economy that had been growing rapidly since 1990-91.

- However, the momentum was lost within two years. GDP growth slowed significantly in 2016–17, most likely as a result of demonetisation in November 2016.

- The growth rate continued to slow until the sharp rise following COVID.

- Since 2014, the growth rate has not increased, despite the fact that the Indian economy has grown to become the fifth largest.

- If we extend the trend growth rate of 5.5% achieved in 2016–17 to 2022–23 and 2023–24 and compare it to the actual figures, we are 2.5% lower for 2022–23 and 1.3% lower for 2023–24.

The reality of post pandemic economic recovery

The government has claimed that we are witnessing a robust economic recovery following the pandemic, demonstrating the strength and potential of the Indian economy. This does not hold up under closer scrutiny. In reality, this recovery is merely a rebound from the contraction caused by the pandemic.

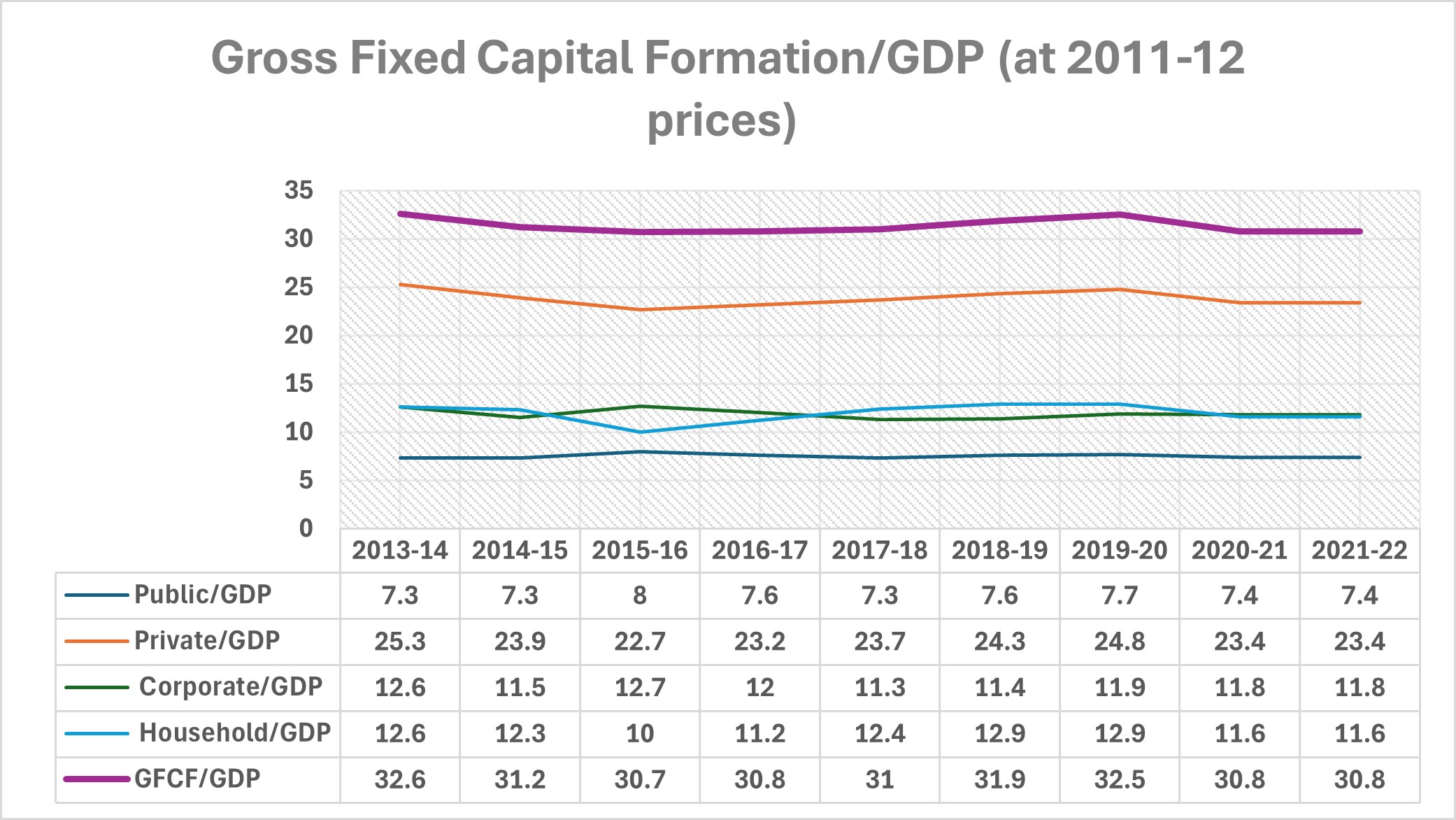

As shown in the chart and data below, the investment rate, Gross Fixed Capital Formation (GFCF), has not increased since 2014.

Key observations:

- the investment rate has been consistently lower than the 32.6% seen at the start of Modi’s tenure in 2014. The investment rate peaked at 34.3% in 2011–12 and then has been sliding.

- The current government has been unable to halt the decline in investment.

- Even a significant reduction in corporate tax rates in 2019 did not result in higher investment rates, indicating that investors are skeptical about India’s current economic policy and growth story.

- Employment Status

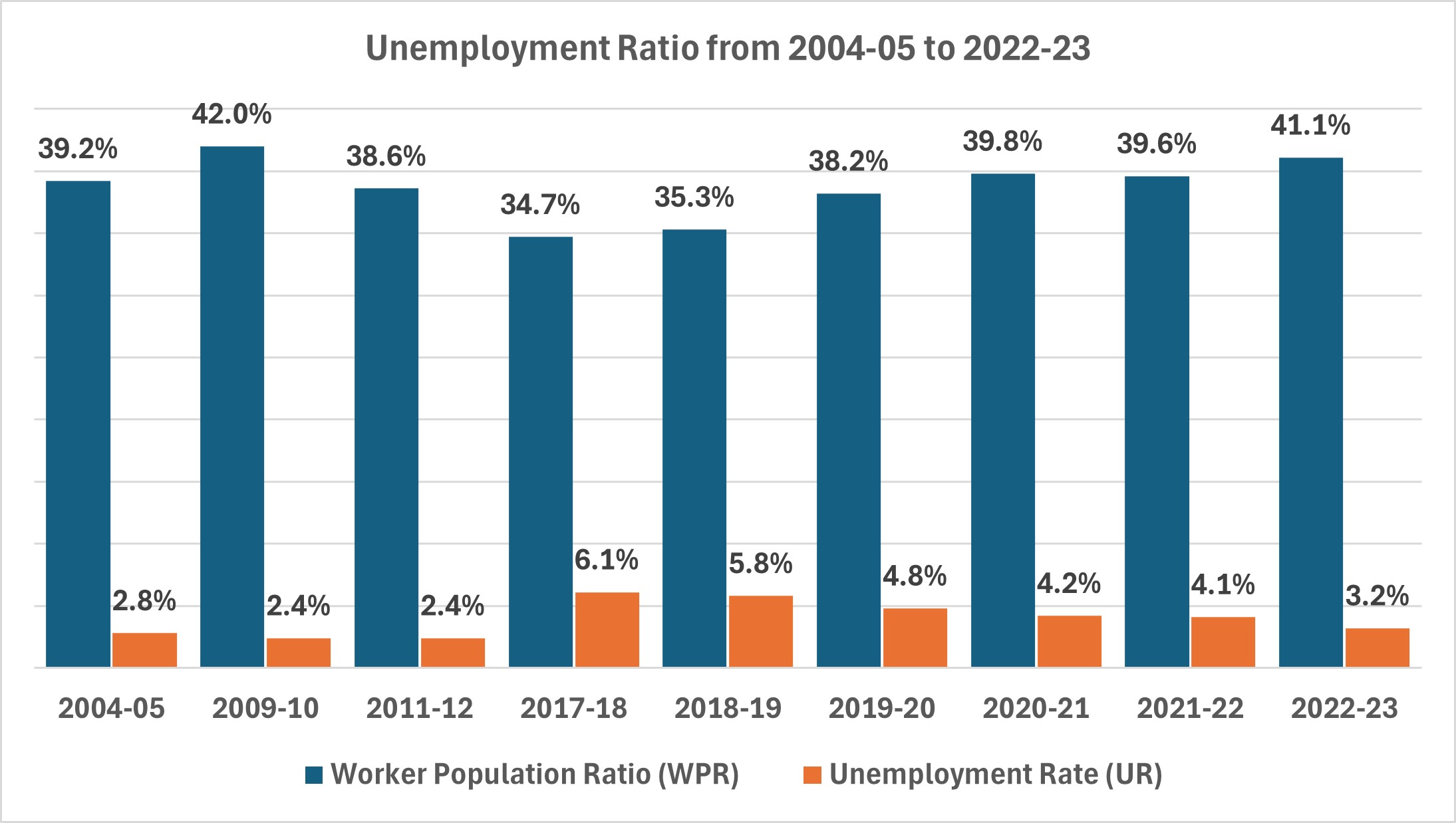

The Modi government came to power with the promise of creating two crore jobs per year. The actual numbers say a different story.

Unemployment Rate

As shown in the chart below, the unemployment rate, a standard criterion used to assess an economy’s performance, remained higher during Modi’s tenure than in previous years.

Note: A continuous data series on both UR and WPR is available only from 2017-18 onwards. Data are for usual (employment) status.

Source: WPR is from the Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) for 2017-18. UR for the years up to 2017-18 is calculated from data in PLFS (2017-18). For later years, it is taken from subsequent annual issues of the PLFS.

Key Observations

- Although the worker population ratio (WPR) remained relatively stable, the unemployment rate (UR) increased dramatically from 2014 to 2019, peaking in 2017-18 due to demonetization.

- Over the past decade, the unemployment rate has remained stable.

- Instead of 2 crore jobs being created each year, the Modi government has eliminated many jobs (or unfilled positions) in the government and public sector enterprises over the last ten years.

Impact of ‘Make in India’

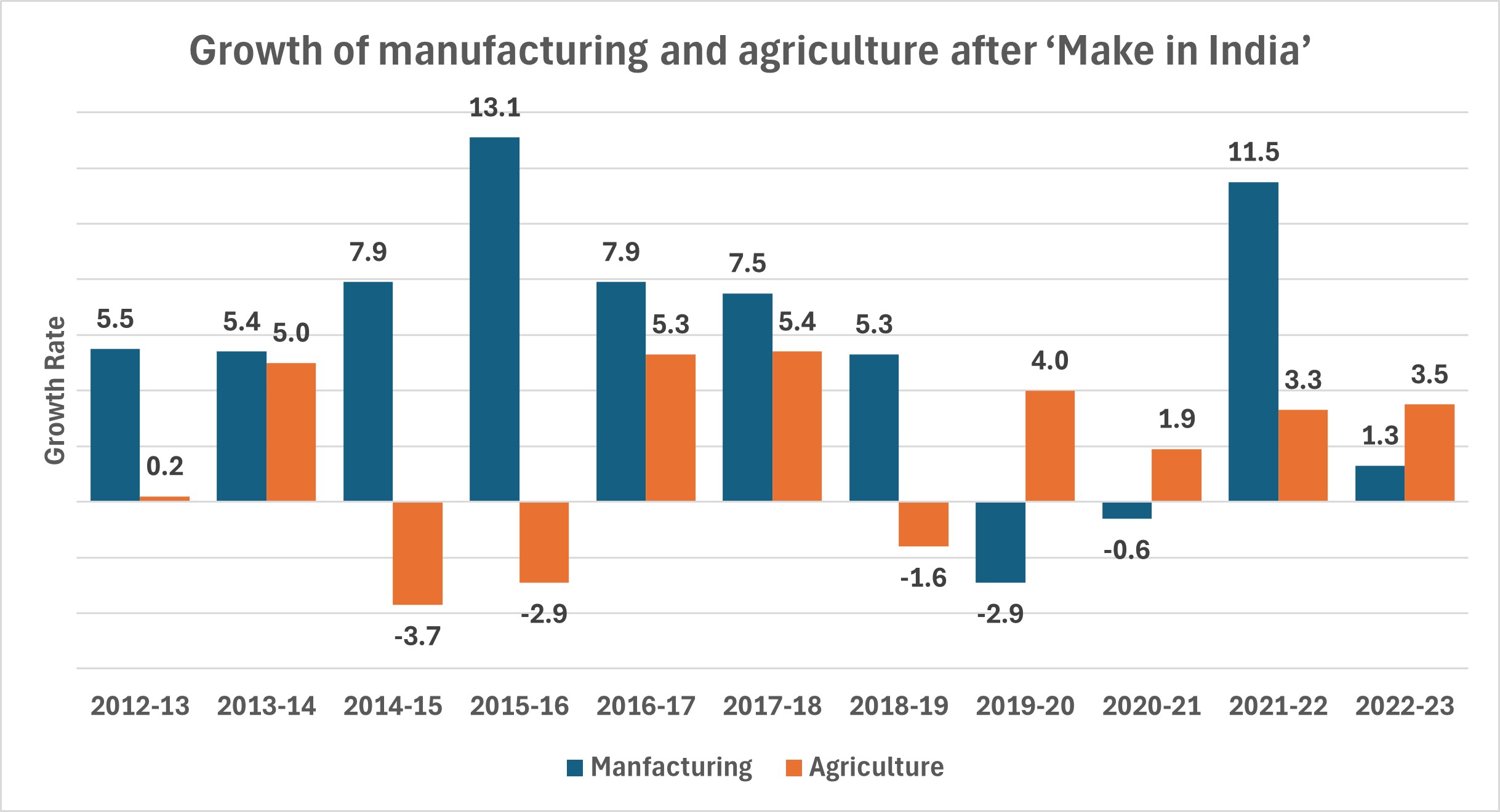

“Make in India” is a flagship programme Narendra Modi launched in 2014 to facilitate investment to build best in class manufacturing infrastructure in India. The programme has a strategic intent of inviting global corporations to manufacture in India and thereby providing a fillip to foreign direct investment. It aims to create 100 million additional jobs and raise the manufacturing sector’s contribution to GDP to 25%.

But data shows that “Make in India” did not lead to growth of manufacturing and has had no significant impact on India’s economic growth during last decade:

Key Observations

- Make in India has had no positive impact on the rate of growth in manufacturing.

- Since 2016, the rate of growth in manufacturing has declined, again a fallout of demonetization.

- Had agriculture not shown significant growth in 2016–17, the impact of demonetization would have been even more devastating.

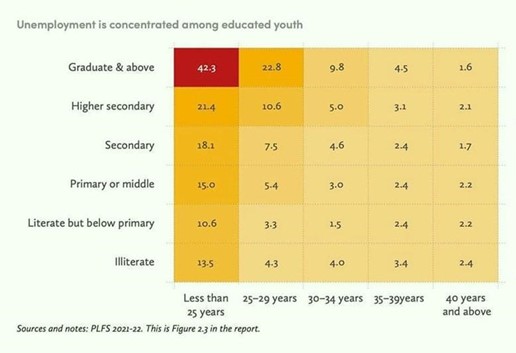

Unemployment status grouped by age

The data from the Periodic Labour Force Survey (2021-22) shown below demonstrate the dire state of employment in India.

- Poverty

The government did not release the status of the National Sample Survey Organization (NSSO) survey conducted in 2017–18 as it would not have supported its narrative for the 2019 elections. Ever since, there has been no authentic measure of consumption poverty. The consumption expenditure survey conducted by NSSO has historically been the most authentic way to measure poverty.

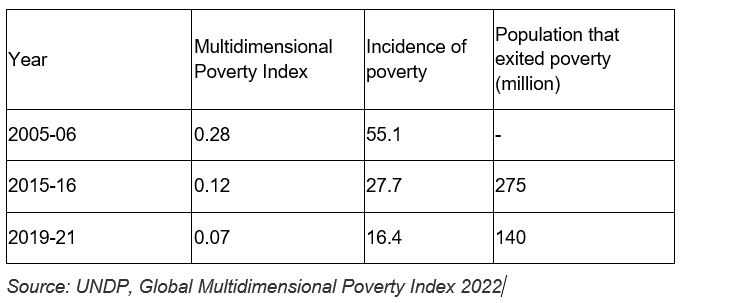

Multidimensional poverty index

The multidimensional poverty index produced by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) shows the deprivation index of individuals. As per the table below, the rate of decline is not greater than what it has been since 2005.

Additional Observations:

- Based on the findings from a factsheet on the findings of a survey of consumption expenditure undertaken in 2022-23 , Per capita rural consumption growth has remained unchanged in real terms over the period 2012-13 to 2022-23 compared to that registered during 2000-01 to 2011-12.

- The growth rate of average urban consumption in real terms, declined over the same time span.

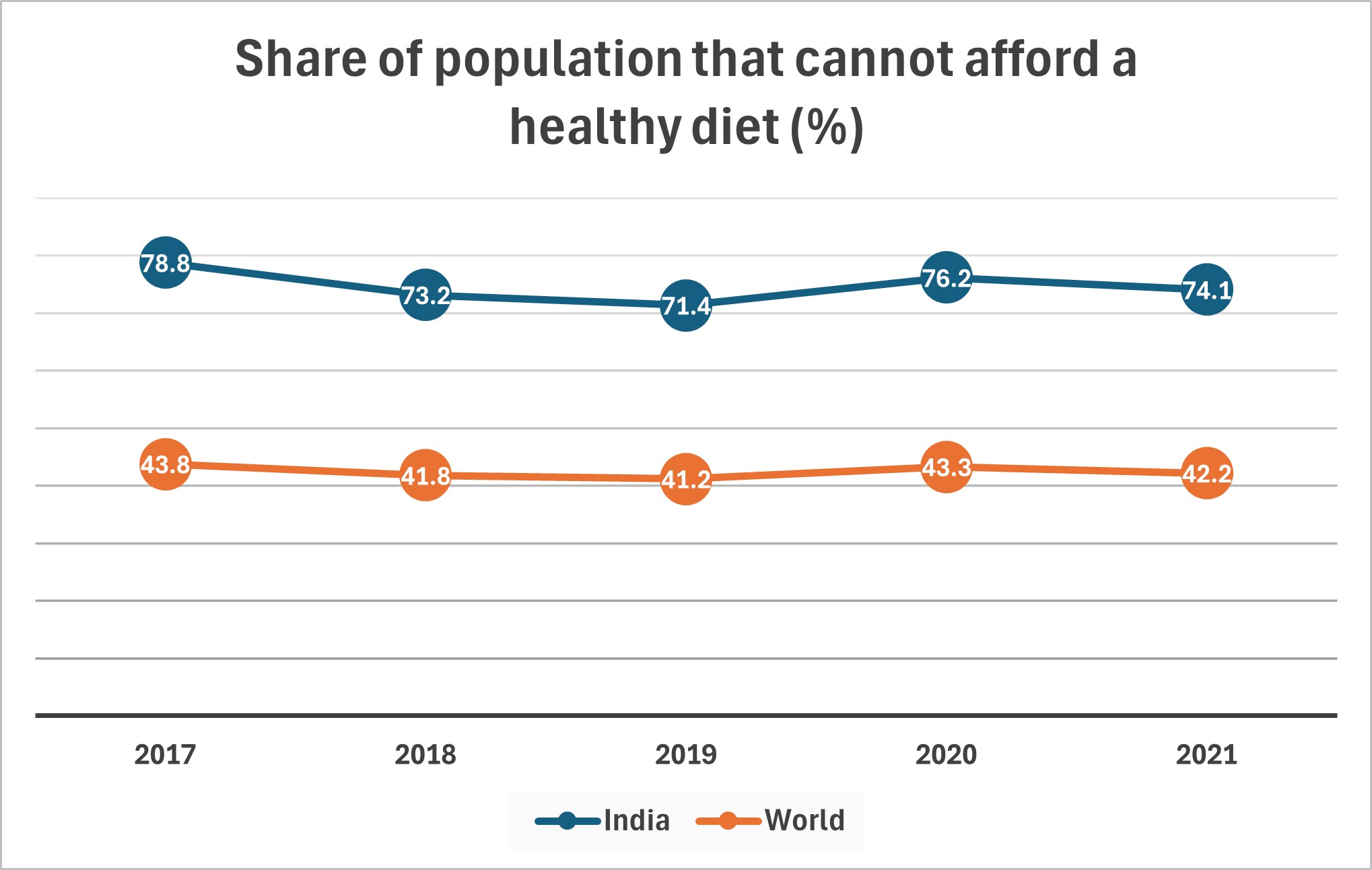

Food security

As per the data issued by Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), 75% of the population cannot afford a healthy diet.

Source: FAO (2023)

Key Observations

- 75% of our population cannot afford a healthy diet. This is significantly higher than the global average, which is in the 42–44% range.

- PDS system hasn’t helped improve the situation. A low inflation rate also has not helped improve the situation, which seems to indicate that even at low price inflation, essential food items are not affordable for 3/4th of the population.

- Such an abysmally low percentage is not finding any place in any serious discussion on Indian economy, which is being celebrated for being the 5th largest and the fastest growing one currently.

The “Sabke saath Sabke vikas” story

Income and wealth distribution

What is the status of income and wealth distribution or inclusive growth, as the slogan “Sabke Saath Sabke Vikas” claims? A growing economy must be inclusive; however, the absence of official data indicate that our government doesn’t keep track of this metric. Even in the World Inequality Report, entries for India end with the year 2019.

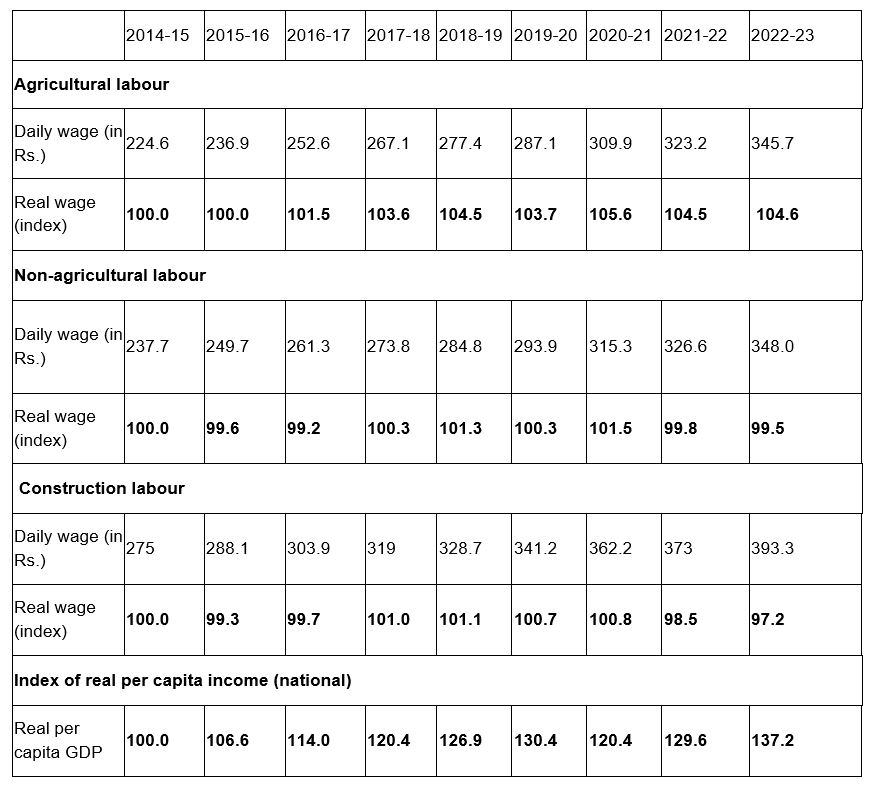

Table below provides indicators of income and wealth distribution. The distribution is calculated using the data on wages in India. Surprisingly, there is no such data available for women.

Sources: (i) The real wage has been calculated from Labour Bureau Data data on wages and the Consumer Price Index for agricultural workers published by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI). (ii) Real GDP data are from the National Accounts Statistics, Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation.

Key Observations

- There is a slight increase in agricultural wages until it peaks in 2018–19, and then it remains stagnant.

- Even this increase of 5% is dwarfed when compared with the growth of per capita income, which is at 37% for the period 2014–2023.

- The condition of non-agricultural and construction labour income is even worse.

- As per the Sixth Economic Census of India (2016), 51.7% of Indians are employed in rural areas, of which 68.9% are non-agricultural workers, which means that for 35% of India’s workforce, real wages have stagnated since 2014.

- In 2022–23, the daily wage of an agricultural worker was only 2/3rd of per capita income of the country on an annualised manner. The per capita income grew approximately nine times faster than the real wage of these workers, suggesting that the income inequality gap is widening very fast.

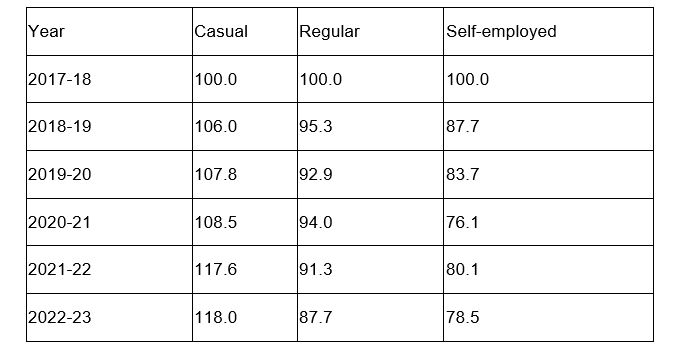

Growth of earnings

The table below shows the movement in real incomes based on the Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS).

Note: Earnings are indicated as index numbers, with the base year 2017-18 equal to 100.

Key Observations

- As per the PLFS data, only the real earnings of casual workers have risen marginally. For others, it is a decline.

- The PLFS data also categorizes casual workers at 21.9%, regular workers at 20.8%, and self-employed at 57.3%. This implies that for a whopping 78% of the workforce, the real earnings have declined since 2017–18.

References:

The charts and / or the data for the charts and analysis are taken from the following articles. The complete article, along with detailed analysis, can be read by following these links. These articles are written by Dr. Pulapre Balakrishnan and Dr. M Parameswaran.

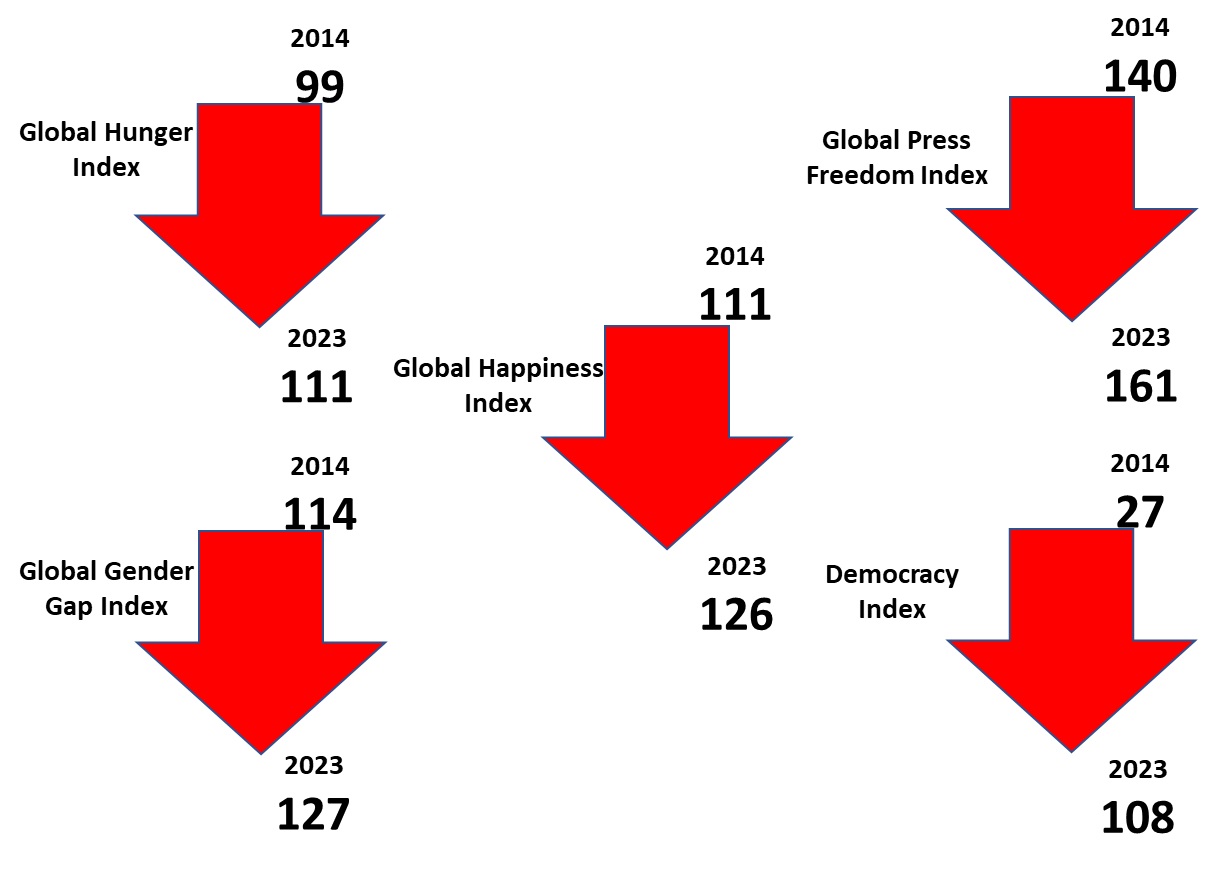

Drop in all major global indices.

Manoj K C : An engineer of 1989 vintage and still getting paid. A nonbeliever of rational agent model humans. Though convinced that it is all about biases and emotions, he insists on letting data speak, who knows, someone might be listening!!