G.P. Ramachandran

Within two years of India’s independence, the Central Government appointed a commission to decide on the government’s approach to cinema. This committee, called the Film Inquiry Committee, was formed in 1949. The report of the commission, with SK Patil as its chairman and M Satyanarayan, Dr. RP Tripathi, V. Shankar, V. Shantaram, and BN Sarkar as members, was submitted in October 1951. Though several very important recommendations were submitted by the SK Patil Committee, the majority of them were not implemented by the government. It was a massive report, numbering about four hundred pages. It contained proposals that could be broadly divided into three categories: strengthening the film industry in India, providing assistance to overcome its existing drawbacks, and others. The most important proposal was that the government should set up a Film Council to control and supervise the film industry. The essence of the committee report was that the future cinema of independent India should be widely and permanently controlled and determined by the government as a guide, friend, and philosopher. The report recommended that the proposed council consist of representatives of the government as well as spokespersons of producers, distributors, exhibitors, artists, technicians, workers, teachers, and economists. The report also recommended that a technical code administration (Production Code Administration/PCA) be established for production. Scripts should be submitted to this PCA for production approval, and the script evaluation should be conducted based on the criteria of upholding public morals, good character, and educational values. This system should also decide whether the respective films are appropriate to be screened abroad. All these important proposals were turned down by the central government, which Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru then headed. When we think about it today, we will be convinced of its wisdom without the need for an explanation.

However, the government accepted some other recommendations from the SK Patil Committee. Prominent among them was the establishment of a Film Finance Corporation to finance film production and an institute to teach cinematography. The Film Finance Corporation was then formed and later became the National Film Development Corporation (NFDC). A film institute was established in Pune. Also, the government accepted the recommendations that film awards should be introduced in India itself, the government should take the initiative to produce films for children, the film division should be strengthened, and prints of good films should be collected and preserved. In other words, the Nehru government adopted a prudent and far-sighted approach to turning down what deserves rejection and welcoming what merits acceptance.

Recently, there have been some developments that bring all this to mind. Four important government institutions that had been functioning for decades have now been merged into the NFDC, ending their independent existence and functions. Although the government orders regarding this came out at the beginning of 2022, the implementation came later. Thus, the Films Division (FD), the National Film Archives of India (NFAI), the Directorate of Film Festivals (DFF), and the Children’s Film Society of India (CFSI) merged into the NFDC. This decision was widely opposed by people from the film industry and outside but to no avail.

The primary reason given for this action was that all these terminated entities were loss-making enterprises. This is a flawed argument that treats cultural institutions on par with industrial institutions. The vital and historic contribution these institutions played in the modern nation-building of independent India has been nullified by a single decree and subsequent merger. In the past, these institutions have made significant and experience-rich contributions in the fields of production, dissemination, and accumulation. To forget these is equivalent to erasing the memory of the nation itself.

We are all aware that cinema is the most popular medium capable of shaping public opinion. Mixing true events, fiction, half-truths, and outright lies is nothing new in cinema. The only thing we can do in this predicament is to spread a critical, historically informed, and democratic approach to cinema in general and to individual films in particular, among both viewers and non-viewers alike.

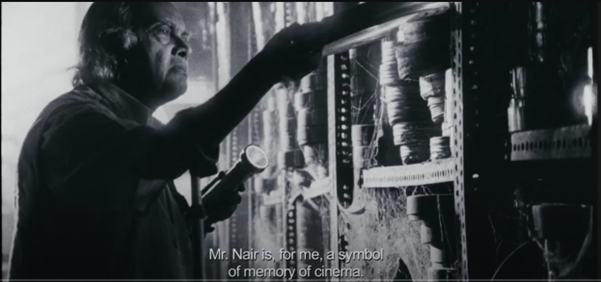

The journey, which started in 1964 with 123 films, increased to 12000 when PK Nair retired. In his opinion, even that is very small, considering the vast history of Indian cinema. In an era in which films were not even recognized as part of the cultural tradition, film archives and the tens of thousands of exhibitions organized by film societies and others, with their help, have paved the way for bringing cinema to the most critical place in our intellectual/ cultural/ learning/historical/artistic spheres. Now all this will be nothing but memories.

It is a shocking realization that India, the nation that produces the most films in the world, will no longer have a film archive. Every major country, including the US and France, spends billions of dollars and euros collecting films, both their own and not. What is really needed is to start more archives in India. Mumbai, Chennai, Kolkata, and Hyderabad all have different filmmaking histories. If they are lost by any chance, then where do we search for Indian cinema and India? The National Film Archives of India may never be financially profitable. But who will tell the government that culturally and historically, the process of nation-building and the archival of cinema as its indispensable component are projects of vital importance? Indian cinema’s digital past may end as a fading memory in NFDC’s profit and loss accounts.

The National Film Development Corporation, the successor of the Film Finance Corporation, extended financial support to many films that were produced between the seventies and the nineties. The New Wave, or Parallel Cinema, or Modern Cinema in Indian cinema was made possible through this. Most of these films have won awards both within and outside the country and have been screened at festivals around the world. Undoubtedly, several films that combine the social realities of India with artistic excellence have come about with the help of NFDC. However, NFDC did not make any efforts either to distribute these films through appropriate channels or to set up the government’s own screening network and screen them through it. In the end, it all boiled down to financial loss, especially in the context of public awareness of liberalization policies. Four institutions, which were once the pride of the nation, are now tied together and brought to this plight.

The Films Division has produced and collected hundreds of documentaries marking the art, history, and culture of independent India over the past seven decades.

The Films Division was established in 1948 by merging the Film Advisory Board created by the British government in the 1940s, the Army Film & Photographic Unit, Information Films of India, and the Indian News Parade. The Film Advisory Board was created to carry out British propaganda during World War II. Needless to say, its renaming and evolution were synonymous with the nation’s independence. As BD Garga explains in his books, the films of the Films Division helped to make independent India better understood by the people, both within and outside the country, and perhaps even by the rulers. Eight thousand and five hundred films have been produced by the Films Division during this period. Whether all those will be archived and made available to researchers who may need them has become an uncertain reality. The only remaining visual records of pre-television India are the documentaries in the Films Division. There is a mandatory requirement that newsreels and other documentaries produced in sixteen languages be shown before feature film screenings. Moreover, the theatre owners had paid the rent for this to the government. Through this, the Films Division had earned an income of crores of rupees.

Despite being a government propaganda machine, the Mumbai International Film Festival of Short Animation and Documentary Films (MIFF), held every two years in Mumbai by the Films Division, is an internationally acclaimed one. Despite the government and censors controlling this film festival in recent times with strict restrictions, a rich past comes to the memory of moviegoers. I too have a fond memory of participating as a delegate at MIFF in the early 90’s as an official guest. On that occasion, Anand Patwardhan’s War and Peace and P Balan’s 18th Elephant received awards. Although pro-government, the Films Division has produced hundreds of documentaries on industrialization, agriculture, health, education, and housing. The biographical documentaries produced by the Films Division on prominent personalities in the fields of art, culture, politics, and science are also prominent.

Most of the regional offices of the National Film Archives and Films Division have been closed down since its merger with the NFDC. The collections housed in them are likely to be destroyed. And with that, a diversity of viewpoints will become impossible. There was a plan to select and watch FD films in nine cities, including Mumbai, under the name of FD Zone. With the closing down of local centers, this too will no longer be possible. As documentary filmmaker Avijit Mukul Kishore recalls in his Scroll article, JBH Wadia, Ezra Mir, V Shantaram, BD Garga, Jean Bounagari, S Sukhdev, SNS Shastri, Vijay Mule, Pramod Patti, Vijay B Chandra, Loxen Lalvani, Satyajit Rai, GL Bharadwaj, Ritvik Ghatak, Mani Kaul, V Pakirisamy, Joshi Joseph, Kamal Swarup, Anirban Dutta, Renu Sawant, and Farah Khatoon were all independent filmmakers who directed films of the Films Division. Even though they may be pro-government propaganda documentaries, they do function as checkpoints in cultural history. By breaching it, the collection and continuity of the visual tradition are lost.

The government, which found Air India to be loss-making and sold it to private investors, may not hesitate to disinvest NFDC, finding it too to be loss-making. On a recent visit to Kolkata, while talking to Dr. Kochukoshi, a retired senior librarian of the National Library, he narrated an incident that took place there. The National Library is one of the most important and extensive libraries in the world. Several years ago, the Ford Foundation made a proposal: They would digitize all the books in the National Library at no cost. They had just one condition. They will keep a copy of it. The government disagreed with this in principle and rejected the proposal. It is not possible to imagine what will happen to the National Library, Film Archive, and Films Division in the future when everything will be evaluated only on a profit-and-loss basis and the rest will become forgettable.

Mrinal Sen, Shyam Benegal, KA Abbas, MS Satyu, and Sai Paranjpe have all made films for the Children’s Film Society, which was founded in 1955. Children’s film festivals were also held.

The Directorate of Film Festivals was established in the 1950s to manage international film festivals and national awards. The role played by the DFF in developing a good film culture in India is invaluable. As part of the National Awards in 2006, I received the Golden Lotus for the best critic. After this, I was able to be a member of the jury for the National Award for Writing in 2007. Being able to attend meetings at the DFF headquarters in Sirifort and participate in the process of national award selection convinced me of the transparency of the process. Now, when it comes to the environment where NFDC itself decides the film awards, one wonders what would become of its course and credibility!

Distinguished documentary director Anand Patwardhan stated that we should realize that all these are not things that should be measured for economic reasons, but efforts to rewrite history and an ideological struggle within cinema. Hundreds of filmmakers in the country tried their best to speak up against this merger, acquisition, and closure, but no one bothered to pay attention. John Brittas, MP, raised this issue in the Rajya Sabha. It was on this intervention and other demands that the initially recalcitrant government published the Bimal Jhulka Report, which recommended this closure and merger. In an article written in this regard, director Joshi Joseph who is also a former Films Division officer, disclosed that only Chairman Bimal Jhulka and a Joint Secretary have signed the report. The other members—directors AK Bir, TS Nagabharana, Rahul Rawail, and Shyamaprasad—have not signed.

The government’s film institutions were envisioned to explore and mark the great achievements of local, national, and international film culture, introduce Indians to them, and positively transform cinema in India. With the loss of their independent existence, the future of the nation becomes bleaker.

The International Film Festival of India (IFFI) 2022 witnessed an event that reiterated just how critical it is to the independent thinking and existence of India and Indians. Nadav Lapid, who was the jury president of the 2022 International Film Festival of India (IFFI-Goa), explained how Kashmir Files is a cinematic manipulation. Its use of sound and images, the way visuals are constructed, and the distinction between good and bad people are all problematic. The film is based on extremely complex and distressing events. So, we need to be more alert. We also need to be more judicious. Lapid is not saying that controversies or disputes should not come in films. There are controversies and disputes about the themes he chooses. The problem lies in how they are approached.

Sanjay Kak, a documentary filmmaker who is also a Kashmiri Pandit, wrote in an article for Al Jazeera about Kashmir Files: The film’s political capital was to acknowledge its claim to truth and to point out that these truths had been covered up for so long. In the months since mid-1989, when some important figures of the Hindu community were killed, spreading widespread anxiety and insecurity, a large number of Muslims, including political activists, policemen, and government employees, were also killed. It was all part of the political conflict of the time. Kashmir Files, however, wades through assertions and ambiguities that nothing less than the Kashmiri genocide took place. The evidence claimed in it is said to have been gathered orally from 700 first-generation victims. It is re-examined by ‘authoritative’ historians, academics, administrators, and police officers, catering to the interests of the makers of the film. This is why it did not surprise me when the presenter of this film stated, ‘This film does not claim any historical accuracy’. ‘The Kashmir Files’ has the potential to make it appear for at least three decades that this is the only truth about Kashmir that the right-wing claims to be. By including extreme violence, it creates a narrative in which no other interpretation is possible, even what we know to be true, thereby engendering cruelty in the viewer. I have come to understand that, even though many have faced terrible hardships, most Kashmiri Pandit families have not been betrayed by their Muslim neighbours. Although some properties were looted and destroyed, most temples and houses were neither looted nor destroyed. Many have later perished from years of neglect. Some elements in the media, bureaucrats, and police may have been negligent in their responsibilities, but they did not collude in persecuting the Pandits, as the film suggests. By constructing truths about Kashmir from beyond the scraps of fact and mixing them with a provocative fictional narrative, Kashmir Files hints at a larger agenda. Ultimately, Kashmir Files is not about establishing a historical record of Kashmir in the 1990s or creating an environment that would facilitate the return of a community in exile. Instead, the demonization of the Kashmiri Muslim narrative makes reconciliation much more difficult. By avoiding Kashmir’s complex 700-year history and linking it to the idea of a return to the glorious past of Kashmiri Pandits, the political project sows the seeds of a Hindu homeland. It is a concept somewhere between eviction and resettlement. And that is what makes the ‘truth’ in this film so dangerous.

Fascists are using the age-old strategy of ‘isolating and owning’ in Kerala to capture it. Part of this is the move to make a film called Kerala Story (Director: Sudipto Sen), which is constructed on a pack of lies. In 2018, the same director released a documentary, In the Name of Love -Melancholy of God’s Own Country, which had love jihad as its theme. Seventeen thousand girls were shown to have converted to Islam and joined ISIS.

It is clear that behind this is an anti-social conspiracy to spread the culture of riots, hatred, and violence in Kerala. In the trailer of this film called Kerala Story, it was said that thirty-two thousand girls were converted in Kerala, who then joined ISIS and were sent to Syria and Yemen. Following widespread opposition, this figure of thirty-two thousand was later changed to three.

The true story of Kerala is that in the indices of quality of life, social indicators, and health system, Kerala can compete with developed nations. Secularism, peaceful rule, tolerance, pluralism, democracy, and progressive thinking are all hallmarks of Kerala.

Freezing the internet is a practice adopted by the government whenever there is unrest in society. Whether it is right or wrong is another matter. This ban is done when the government feels that things are out of control. In India, the internet has been shut down 418 times since 2012 in Jammu and Kashmir. The internet shutdown was done 97 times in Rajasthan, 31 times in Uttar Pradesh, 20 times in West Bengal, 19 times in Haryana, 16 times in Meghalaya, 15 times in Bihar, 12 times in Maharashtra, 11 times in Gujarat, 10 times in Odisha, 8 times each in Punjab, Manipur, and Arunachal Pradesh, 7 times each in Jharkhand and Madhya Pradesh, and 5 times each in Assam, Nagaland, and Tripura, 4 times in Delhi, 3 times in Telangana, and 2 times in Uttarakhand. The Internet ban was implemented only once in Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Himachal Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh, and Chhattisgarh. Kerala, on the other hand, did not need this drastic measure even once. What more proof is needed of the atmosphere of peace that has prevailed here for the past ten years? The Internet has not been banned in Sikkim, Ladakh, Chandigarh, Puducherry, and Goa during this period. Most of these are union territories. The population is incomparably smaller. So, what could be the reason for artificially creating religious intolerance, hatred, and false accusations about Kerala?

The allegation of love jihad, which incidentally was rejected by the courts, the Central Government, and the Kerala government, is the basic premise of this film. The precise purpose of the allegation of love jihad is to perpetuate an attitude of suspicion and alienation towards the Muslim in the social unconscious of the Keralite mind, which is aflame with a sense of democracy, patriotism, and independence.

On the many romances that usually take place in the country, these love jihad propagandists cast a dark shadow of doubt, thus leading to genocide. The fact that newspapers, channels, public consciousness, and community organizations were ready to aid and abet the Sangh Parivar agenda to victimize lovers, inter-caste and inter-religion couples, and religious converts, in addition to the three declared enemies—Muslims, Christians, and Communists—made matters more serious and caused them to spin out of control.

By an accusation of being Alien or the Other, by general society and small and large groups, there is a growing tendency in modern times to separate, isolate, and blame a person, a community, a culture/a language/a place/a faith. The press and TV media, while acting as a form of authority in themselves, have already become the main arena for this practice of alienation. The Far Right is trying to continue the spread of this poison through continuous activity in cinema as well.

Secularists believe that religious conversion is a matter of individual freedom. This view is based on the Constitution of India, which was formed under the leadership of Ambedkar. He realized that there was no salvation for the Dalit masses in Hinduism and, therefore, towards the end of his life, converted to Buddhism in a public forum, along with hundreds of thousands of his followers. The common people of Kerala were able to accept with tolerance, brotherhood, and love when Malayalam’s beloved storyteller, Kamala Das, or Madhavikkutty, changed her name to Kamala Suraiya and accepted the Muslim religion. Some extreme Hindutva communalists tried to stir up trouble, but it was dismissed by the general public. The United Nations Declaration on Human Rights states: “All human beings shall be free to exercise their own interests in matters of thought, conscience, and religion. This right includes the freedom to change one’s religion or belief “(Article 18). It is then clarified that it is wrong to force someone to convert. At a time when religious conversion is raised as an issue of culture and nationalism and is symbolized by fascism as a counterargument to genocide, the conceptions and imaginings of religious conversion also cloud the issue of alienation. Hysterical nationalism assigns to these others the status of unfitness for the common law of society, or as those who must be relegated to a lower rung in the general hierarchy. Religious and linguistic minorities, Dalits, and foreigners all face this threat of alienation in India now. Kerala Story tries to push all Keralites into this otherness.

The fact is that Love Jihad is a propaganda frenzy concocted as part of an overt and covert plan to subjugate Kerala to an aggressive Hindutva ideology, on similar lines to Gujarat, Orissa, and Karnataka.

Former Minister of State for Home Affairs and current Union Minister G Kishan Reddy has answered in the Parliament itself that there is no such thing as Love Jihad. Yet by deliberately making this false accusation the main storyline of the film, we understand it to be a move to demean and humiliate Kerala among the people of other states in India. It is likely to destroy religious harmony, divide Kerala on religious lines, and make Keralites as a whole be viewed with skepticism and contempt in other states of India.

At the 2022 Goa International Film Festival, International Jury President Nadav Lapid publicly criticized the inclusion of the controversial film Kashmir Files in the competition category. All but one of the jurors voted in favour of Nadav Lapid. It may also be remembered on this occasion that Sudipto Sen was the only jury member who disagreed with the chairman.

All the uproar goes on to prove that only by exercising vigilance can we protect Kerala and Kerala’s democratic, secular, progressive conscience.

SS Rajamouli, the director of Baahubali and RRR, considers himself to have developed his investigative journeys and storytelling/narrative skills from Amar Chitra Kathas, which he started reading at the age of seven. He thinks that Amar Chitra Kathas are not just about a superhero but are a vast ocean of storytelling traditions full of folklore, mythology, epics, legends, and beliefs, all of which comprise the culture of India. “Those stories full of castles, great kings, and wars have always fascinated me. Not only did I enjoy reading them, I made up new stories with my own style of presentation and narrated them to my friends.” In short, Baahubali 1 and 2 are extensions of the childish fantasy that has been firmly rooted in Amar Chitra Katha. RRR is also a re-imagination of the freedom struggle as a children’s story. Considering that fascism is characterized by a childish simplicity that rejects the political complexities of experience and historicity, the extreme triumphs of Baahubali and its sequels are not at all anachronistic. Vijayendra Prasad, the screenwriter of RRR and Baahubali, is working on the script for a big-budget film on RSS. Apart from this, a series on RSS is being prepared by six directors, including Priyadarshan. All this will be completed by 2025, the centenary year of the RSS. Titled One Nation, Ek Rashtra, the poster of the series depicts a Shakha member in khaki trousers, facing away from the viewer.

Baahubali’s takeover of the Indian film market and the Indian film market abroad just before the implementation of GST with the slogan of ‘One Nation, One Market, One Tax’ also marks the success of marketing, public relations, and advertising. Baahubali exhibits a duality that simultaneously embraces and rejects local cultures and languages. They are dubbed and adapted into all languages. At least for the time being, smaller films in those languages are either frozen or pushed aside. The repercussions of all this in the coming days will need to be examined. Over and above everything, Baahubali leaves a clear message that Indian mainstream cinema, though it started out with Hindu mythology but has remained secular to a large extent, is not going to remain secular in the turbulent times ahead. This is the most disturbing reality.

The protagonists of Rajamouli’s hit RRR are Komuram Bheem (NTR Jr.), a Gond tribal freedom fighter who fought against both the British regime and the Nizam, and Alluri Seetharamaraju (Ram Charan Teja), a Kshatriya leader. The directors and others associated with the movie have clarified that they have taken artistic liberties while turning it into a movie story. This claim is probably made so that the contradictions between RRR and historical reality are not audited. Observers like K Sahadevan, who has meticulously researched the tribal currents of the freedom struggle, expose these deviations as serious historical-political frauds. In the movie, Komuram Bheem says to Alluri Sita Ramaraju: ‘Brother, aren’t we forest dwellers? We know so little.’ The falsehood is thus fed into the general consciousness that tribals are ignorant and uncivilized. Komuram Bheem was a warrior who led the Gond-Kolam tribal people of Adilabad district in the famous Babejhari-Jodenghat uprising between 1938 and 1941 and simultaneously led the battle against the Nizam and the British. He is a leader who raised the slogan Jal-Jungal-Zameen (Water, Forest, Soil) for the forest rights of tribals. Komuram Bhim became a nightmare for the British. The racial and caste attitudes behind depicting this brave warrior as an ignorant barbarian in front of the upper-caste hero need to be exposed. Alluri Sita Ramaraju and Komuram Bheem fought liberation struggles in two different eras and are unlikely to have met each other. Ramaraju in the film has supernatural powers and wears clothing similar to that of the mythological Rama. This character is depicted wearing saffron, rudraksha, and rudraksha and carrying arrows. After going into hiding in Assam and working as a labourer in the plantation area, Komuram Bheem collaborated with the Communist Party, organized revolutionary activities in the Telangana region, and formed the Tribal Council. This is also the history behind how Telangana and Andhra later evolved into revolutionary hotbeds of the Communist Party. This is what this film cleverly cancels out in its formula. In the end credits scene of RRR, pictures of Netaji, Sardar Patel, Bhagat Singh, VOC Pillai, T Prakasam, Kittur Rani Chennamma, Pazhassi Raja, and Shivaji are displayed in honour. But Gandhi, Nehru, and Ambedkar are omitted. There is no need to explain what kind of India is being built into the public consciousness through such narratives.

Akshay Kumar is the poster boy of Sangh Parivar. Akshay Kumar was the hero in some of the films that became vehicles of advertisement for the Modi government through several films like Toilet Ek Prem Katha and Pad Man. Directed by Vivek Agnihotri, the film Buddha in a Traffic Jam attempts to justify the fascist term Nagara Naxals (Urban Naxals). In the Tashkent Files released in 2019, the death of former Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri was used to unleash an onslaught against leftist-secular-socialist ideology. The film Uri: The Surgical Strike, released during this period, also had a clear political purpose. In the 2019 film The Accidental Prime Minister, former Prime Minister Manmohan Singh was portrayed as a victim of the Nehru family’s ambitions to rule. Modi was glorified in the movie PM Narendra Modi. Savarkar is glorified in the film Swatantra Veer Savarkar, which opened on May 28, 2023, when the new Parliament building was inaugurated.

Films like Bajirao Mastani, Padmavati, Manikarnika, Panipat, Kesari, Tanhaji the Unsung Warrior, Pawan Khind, Samrat Prithviraj, Adipurush, and many others glorified Hindu kings and mythological gods and belittled the Mughal rulers. A film on Chhatrapati Shivaji called Vedat Marathe Veer Dodil Saath is also getting ready for release. Ram Sethu, The Vaccine War, The Delhi Files, 72 Hours, Doctor Hedgewar, and Main Deendayal Hoon are also films to validate the Sangh Parivar arguments.

All are aware that cinema is the most popular medium capable of shaping public opinion. Mixing true events, fiction, half-truths, and outright lies is nothing new in cinema. The only thing we can do in this predicament is to spread a critical, historically informed, and democratic approach to cinema in general and to individual films in particular, among both viewers and non-viewers alike. No matter how difficult it is, that has to be fulfilled.

There is a simple yet very precise message we can gain from these events. Keep hatred and animosity away from cinema, which is life itself, and from the life on which cinema is based.

G P Ramachandran is a prominent film critic in Malayalam, He is the winner of the 2006 National Film Award for Best Film Critic. He has received several awards including Kerala State Film Award and Kerala Sahitya Academy Award. He has served as a jury member for National and State Film and Television awards.