R. Rajagopal

The first image shows the front page of The Times of India on August 17, 2011, a day after Anna Hazare started his hunger strike on the Lokpal bill when the UPA-II was in power. Stretched across eight columns – the maximum width usually possible in a broadsheet newspaper — the headline thundered: “Govt can’t stop August Kranti”. (See Image 1)

The headline equated Hazare’s campaign with the Quit India movement during the freedom struggle. “Over 13 days, the main section of the Delhi edition of The Times of India covered the Anna Hazare saga over 123 broadsheet pages branded ‘August Kranti (August Revolution)’, with 401 news stories, 34 opinion pieces, 556 photographs, and 29 cartoons and strips,” Pritam Sengupta then wrote in The Indian Journalism Review.

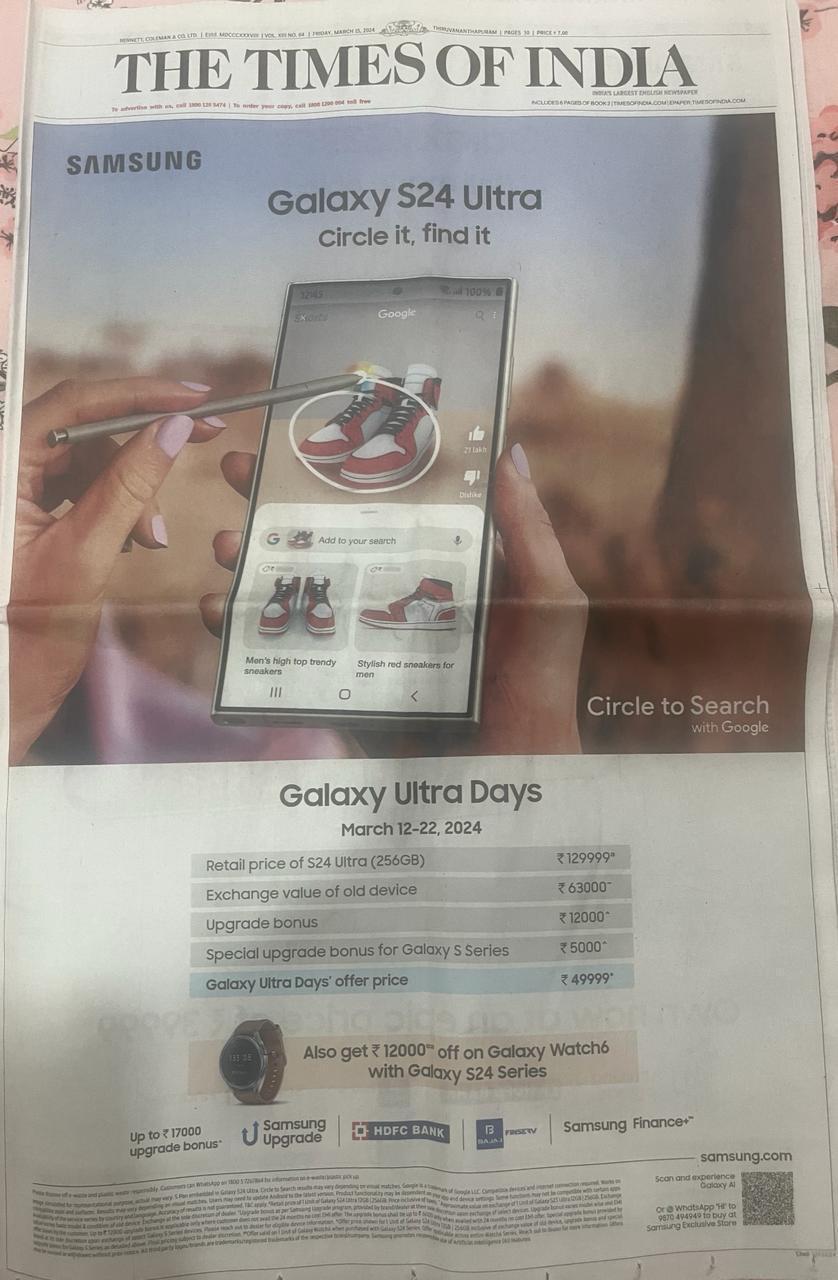

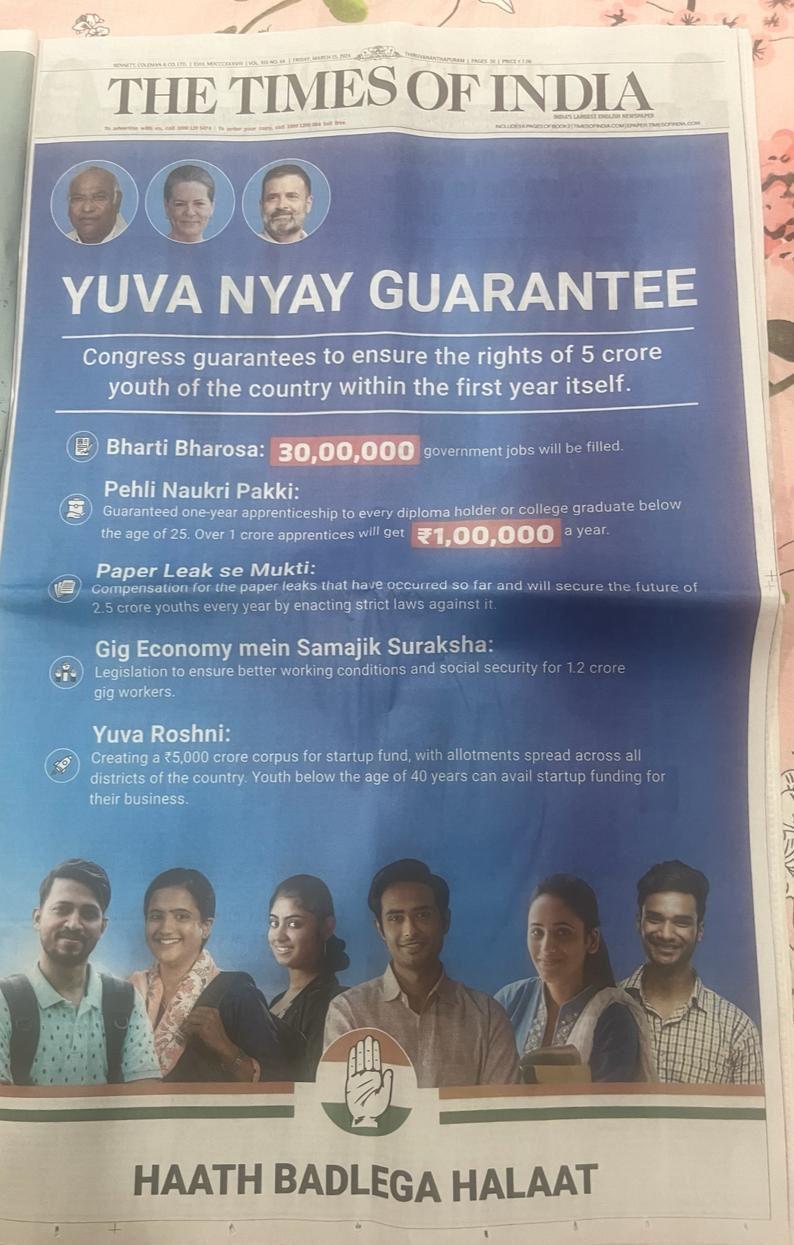

Cut to 2024, March 15, a day after the Election Commission uploaded the initial details of the electoral bonds. The Times of India actually did a better job than many other newspapers but the excitement of the “August Kranti” of 2011 was missing in terms of display and the number of reports published.

“If going to jail in the freedom struggle and the Emergency was such a badge of honour, why is it any less now? Isn’t it time to give back to society and the country now, even at the cost of suffering losses, because the people stood by you all these 75 years and helped you rake in huge profits?”

Unlike the “August Kranti” headline that ran across eight columns in 2011, the electoral bond scandal headline was halved to four columns (see Image 2 set). If the first-day coverage of Hazare on August 17 was spread across “14 pages with 34 reports, 2 opinion pieces, 41 photographs and 1 cartoon”, this is what the leading English newspaper did on March 15, 2024: not more than five reports and five visuals (charts and pictures). Between 2011 and 2024, the concept of the newspaper front page itself had undergone a dramatic change. Strictly speaking, The Times of India’s front page of March 16, 2024, was one or multiple full-page advertisements (in various editions), followed by a flap page and then the page that featured the main electoral bond report. (I am not sure if this was so in the 2011 page.) The Times of India by no means has done anything unique. Most newspapers in India now carry full-page advertisements as the front page, unwittingly returning to the 18th century when advertisements swamped the front pages of several newspapers.

The excitement was missing not just in The Times of India but in several other newspapers, too. I must mention here that I used the images of The Times of India, which is the principal competitor of the newspaper I work for in Calcutta, only because I could not readily find the front pages of other newspapers from August 17, 2011, on the Internet.

The last word on the electoral bonds is still not out and it is a story in progress, although what has come out so far is far more scandalous than any scam we have heard about till now. Perhaps, the newspapers will redeem themselves in the coming days.

The Times of India did step up the coverage of the electoral bonds on March 16. It remains to be seen if the coverage of the electoral bonds will eventually match the sweep of that of the Hazare campaign in 2011. On March 24, 2024, I sought a comment from The Times of India on the perception that the excitement of the coverage of the bonds in 2024 did not match that on the Hazare campaign in 2011 but did not receive a response before I shared my thoughts with this publication.

Whether they do so or not, a far more fundamental change has taken place in many Indian newsrooms since the 1990s when a decade marked by the coinage Typewriter Guerrillas peaked. 1990 is the also the year I became a journalist.

The mask slips

Here, too, images may be more vocal than words.

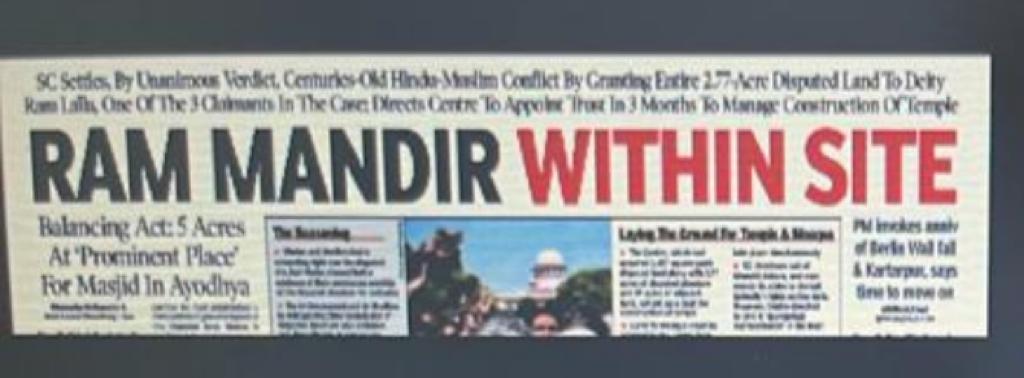

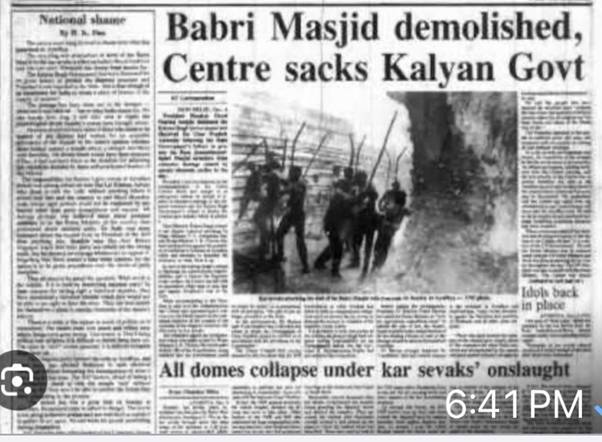

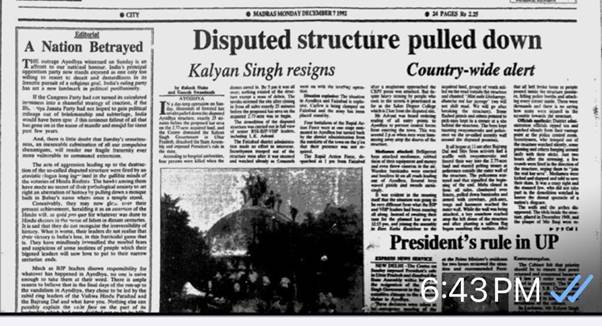

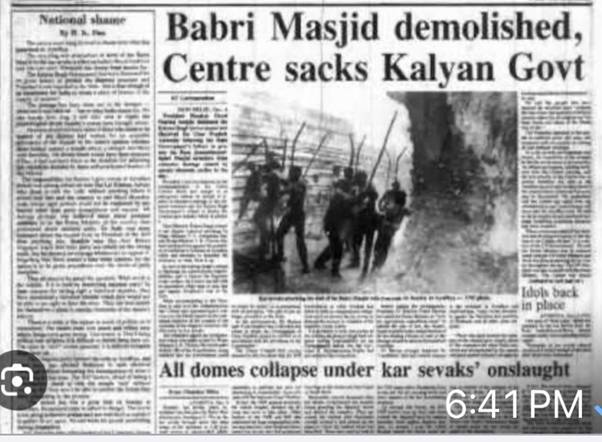

The four pairs of images (Images 6 to 13) show how leading English newspapers covered the demolition of the Babri Masjid on December 6, 1992, and the Supreme Court verdict in November 2019 allowing the construction of a Ram temple at the site where the mosque once stood.

In December 1992, all these newspapers published signed editorials (front-page leading articles that give the opinion of the publication) that unequivocally condemned the demolition of the Babri Masjid. Consider the headlines of the editorials: “The Republic Besmirched”, “National Shame”, “A Nation Betrayed” and “Unforgivable”. It was crystal clear what each newspaper thought about the demolition.

Twenty-seven years later, when the court pronounced its verdict on the same site on which the demolition that shocked and outraged the newspapers took place, there was no sign of any editorial on the front pages.

And when it came to the January 22, 2024, event in Ayodhya, the less said about the coverage the better. Several newspapers were even reluctant to mention “Babri Masjid” prominently.

Deceptive carrot

One of the primary reasons being cited for the media becoming pliable is the lure of government advertisements. I think it is largely a myth as far as big legacy media is concerned, although the survival of small newspapers depends on such advertisements.

In fact, from 2017 to 2023, the Modi government’s expenditure on advertising its policies and programmes in newspapers has plunged by as much as 87 percent, Newslaundry reported, quoting figures from the Union Information and Broadcasting Ministry. “From 2017-2018 to 2022-23, the Times Group saw its (government) ad revenue go from Rs 42.90 crore to Rs 5.45 crore, an 87.29 per cent drop. For the Hindustan Times Group, the cut was 87.55 per cent, for Jagran Prakashan 83.71 per cent, Dainik Bhaskar 86.27 percent, and Amar Ujala 78.58 percent,” according to the portal.

In the Financial Year 23, the value of government ads to The Times of India was estimated to be less than Rs 10 crore (figures published or cited by third parties ranged from Rs 5.45 crore to Rs 9.5 crore). The figures appear minuscule when compared with the group’s total advertising revenue of Rs 4,973.79 crore that year. This suggests that government ads do not account for even 1 percent of the total advertising income of the big group.

Not all newspapers will have such advertising muscle but any newspaper that links its survival to government ads can kiss goodbye to editorial independence. Economic independence is essential for editorial independence.

So, if government ads do not account for a big chunk of a newspaper’s revenue, why does such a publication still act as a lapdog?

Fear is the fall guy

An immediate response to any question on why the media is so government-friendly is “fear”: fear of the ED, fear of the income tax office, fear of the CBI and fear of many such abbreviations — all culminating in the fear of jail.

Such all-pervasive fear begs this question: what are our media barons scared of? Are there too many skeletons in their cupboards that they cannot risk a raid? Have they buried too many bodies in their backyard? If they did, let them face the music.

If they did not, what are they afraid of? In any case, many of the legacy media groups shout from their rooftops the real or imaginary roles of their predecessors in the freedom struggle. They also never tired of claiming that their grandfathers or great-uncles had been jailed while fighting for independence.

As I said on February 27 at a seminar organised by the Cable TV Operators Association in Kozhikode and subsequently elaborated in DoolNews, “media barons had gone to jail mostly for non-journalistic reasons. Opinion is divided on why Mammen Mappila was jailed — whether for Manorama’s journalism or in a banking case that some feel was trumped up because of Manorama’s editorial position. But some of the investors in Reporter TV were certainly sent to judicial custody in a wood-stealing case that had nothing to do with journalism.”

“So, if the media barons could go to jail for non-journalistic reasons, why are they reluctant to do so for the sake of journalism? The jail is the same, regardless of whether you are sent there for felling trees or taking on those in power. That is why I don’t buy this argument that the media barons are scared of jail. Can you tell me of one media baron who has been jailed in the past 10 years? So, it is not the fear of jail but something more is at play that is making media barons and editors turn a blind eye to what is happening in the country, especially in northern India.”

“Besides, the barons are well-insulated now. Most publishers, who used to be the owners themselves earlier, are paid professionals now. Even when some barons have assumed ornamental posts with the editor suffix, the imprint line (which gives details of accountability and the location of printing) these days mostly carries the names of paid employees who are described as editors responsible for the selection of news. The barons are protected. The publishers and editors are held accountable — all the more reason why they must assert their powers.”

Another bogey is the Enforcement Directorate. A constant refrain by potential victims and apologists are the raids on Dainik Bhaskar. But the Covid stories Bhaskar did are still being quoted when any story is done on India’s Covid mismanagement. Nobody can take that away. If Bhaskar “settled” as some claim, that still has not undone the excellent journalism they did when most others were keeping silent. This is exactly what I meant: resistance, however fleeting it may be, can make a difference.

In fact, even after the raids, the Bhaskar group covered the electoral bond story aggressively. The most circulated headline dealing with the electoral bond scam was given by the Dainik Bhaskar: “Netawon ke Chanda Mama (The extortion uncle of politicians)”, punning on the Hindi phrase for the loveable moon.

Corporate stranglehold

Another key suspect in destroying the media is the corporate ownership of so many media outlets, especially news television channels.

But the fact also remains that some of the most popular mastheads in India have always been owned by barons with their fingers in many industrial pies. Jute was the industry that bankrolled some media houses immediately after independence. Later, other industrialists also entered or tried to enter the segment.

Bhaskar is an example of how the “corporate” sector has always had a finger in the media business. As I wrote in DoolNews, Newslaundry then reported, quoting journalists associated with the Bhaskar group, that Dainik Bhaskar “has not always been a beacon of adversarial journalism as it’s being portrayed now, journalists who have had long associations with the paper point out…. One reason for the inconsistency, the journalists argue, is that the Agarwal family that owns Bhaskar is invested in a range of businesses – mining, real estate, hospitality, power, education, construction, advertising, publishing, food processing – which the authorities can, and allegedly do, use as leverage over the newspaper”.

The Ambani-run Reliance, which now owns several TV channels, had also made an attempt to break in to the newspaper business in the late 1980s but could not make much of an impact in spite of the boom in the newspaper business in the next decade. The Observer of Business and Politics, a renamed publication, offered high salaries and tried to poach talent but it did not take off despite the keen interest of Dhirubhai Ambani on having a popular newspaper in his stable.

Mukesh Ambani succeeded whereas his father did not. So did Gautam Adani. The key difference now is oligarchs have taken control of TV news. I am not sure how “successful” their media ventures are but the way some oligarch-owned channels cover news gives an impression that promoting the government agenda, rather than the bottom line, is the principal objective behind their foray into the media business.

Time to give back

There is no doubt that many newspapers are in the financial doldrums. The good old days of profits of “25 to 30 per cent” of the turnover are no longer possible. A more plausible profit rate would be 3 percent. So, should the legacy media endanger itself more by antagonising the government, losing revenue, however small it may be, and courting legal trouble?

Yes, I believe so.

How so?

All these years, these newspapers have lived off their perceived laudatory role in the freedom struggle, earning goodwill and a large number of readers on that premise. They have also made decent profits before 2014. A survey of 35 Indian newspaper groups by the Indian Printer and Publisher over a nine-year period in 2023 showed that they had made a combined profit of Rs 3,199 crore in 2016-17, peaking a trend that began years ago. Of course, such a cumulative figure need not give a fair picture of the entire industry but the sum does reflect the profitability of the big players.

Since then, the Indian newspaper industry has been lurching from one crisis to another: a massive shift of advertising to the digital space that has been dominated by the social media giants, the Covid pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine that pushed up the prices of newsprint. But even amid the gloom, signs of recovery have emerged. I am aware of the extreme financial crisis plaguing small newspapers. My references are not to such papers but the big media houses.

If going to jail in the freedom struggle and the Emergency was such a badge of honour, why is it any less now? Isn’t it time to give back to society and the country now, even at the cost of suffering losses, because the people stood by you all these 75 years and helped you rake in huge profits?

The principal reasons

My contention will remain contentious but I do believe that a toxic and regressive cocktail of class and caste factors is the principal reason that has enfeebled the Indian newsroom when it should have repaid a historical debt of gratitude to the citizens.

The class and caste factors were always there but they have now found a safe and fertile zone to leap out of the newly opened bottle and run riot. The composition of the newsrooms itself will give away this worst-kept secret: how many Muslim editors can you name just like that? How many Dalit editors do you know?

The upper caste, upper-class media establishment has become active collaborators with the Modi regime to revive its imagined past glory and a past laced with entitlements that need not entirely be materialistic.

Power – and if not power, then proximity to power – is the aphrodisiac that keeps many newspaper barons and editors in business. It is an immeasurable quantity that often becomes more indispensable than oxygen itself.

Why else would Kalli Purie, vice-chairperson and executive editor-in-chief of the India Today Group, give such a vote of thanks at the recent India Today conclave where Prime Minister Narendra Modi delivered the keynote address?

Purie said: “The media cannot play the role of the Opposition; expecting it to do that leads to unfair charges of Godi or Modi media. If the Opposition is in disarray, the media cannot be blamed for it. We cannot present another side equally strongly if it doesn’t exist. We are observers in this boxing match, we are not the players. If one side is weak or doesn’t show up, we cannot jump into the ring. This is not fear. This is a matter of rules, roles and competence. We are the medium, we are not the message.”

(Acknowledgements: I have quoted from my interviews with Aarude Ayodhya?, a book published by New Spring Publication, Kozhikode, and with DoolNews. Some of the financial figures are sourced from exchange4media and Newslaundry.)

R. Rajagopal is a former editor and current editor-at-large of The Telegraph. He writes a monthly column in the newspaper. He believes communalism is the biggest threat confronting the country and does not trust neutral journalism in times of crisis. He has no hobbies as his only interest is journalism.