K. J. Jacob

Prime Minister Narendra Modi never misses a chance to tell the world that India is the mother of democracy. That may not gel very well with the history of the idea, but one need not quarrel with him, given that the most populous nation on earth is a constitutional democracy now. India’s arrival on the world stage, which Mr. Modi often refers to, has, of course, something to do with it being a democracy.

However, what has been Mr. Modi’s contribution in his 10 years as prime minister to strengthening democracy and the institutions through which it functions in this country? An honest inquiry will throw up some skeptical answers, starting with Parliament and state assemblies.

There is nothing to show that Parliament, as an institution for legislation and oversight of the executive, has strengthened itself in this period. The first Lok Sabha sat on 135 days but the 17th one, whose term will end in May this year, has had only 55 sittings. The speed with which important legislations were passed in this House and in the previous one, where Mr. Modi was the leader, leaves much to be desired. Parliament hollowed out Article 370 of the Constitution and reduced an Indian state into two Union territories in a matter of two days. The latest was the passage of three criminal law bills that replaced the 19th century laws. Together, they had more than 1, 000 sections, which would impact the lives of every Indian and redefine the entire system of administration of criminal and civil justice. It is imperative that every word is weighed by people’s representatives before they become laws. But the opposition cried foul, saying there was hardly time to go through them. Has democracy been strengthened in this period?

Prime Minister of India Jawaharlal Nehru addresses parliament after Indian independence and partition in 1947. © World History ArchiveThe people of Kerala would remember the statement made by the BJP’s state president that the party would form a government in the state if it won 35 of the 140 seats in the state assembly. That was an open defiance of the idea of electoral democracy and a demonstration of the contempt with which Mr. Modi’s party approached elections and popular choices. The boasting of the local party leader had the backing of the party’s successful operation in several states of India, where elected representatives defected from the parties on whose labels they won and moved over to the BJP, felling the popular government. Almost every state government not run by the BJP is in mortal fear of defection by its own people. This, in effect, dismisses the very idea of elections. Does it enhance the idea of democracy?

Article 1 of the Indian Constitution says India is a union of states. In the Constitutional scheme, the governments in the states and at the centre have specified areas where they are empowered to legislate. State assemblies pass bills on subjects listed in the state list and the concurrent list in the Seventh Schedule of the Constitution. The governors, who are the constitutional heads of the states, have been authorised to sign the bills into laws; The constitutionality of such bills/laws will be examined by constitutional courts, i.e., the high courts and the Supreme Court. The Constitution envisages no scrutiny of the bills at the level of the governor. However, the states ruled by non-NDA parties of late have been witnessing the spectre of the governors sitting on bills indefinitely, rendering the legislative power of the state assemblies redundant. While doing so, the governors in fact exercise veto power over the decisions of the state legislature. Sometimes, the bills are sent to the President of India, who will take the decision as per the advice of the Union government. This, in effect, transfers the law-making powers of the states to the Union government. How does it help advance the cause of constitutional democracy?

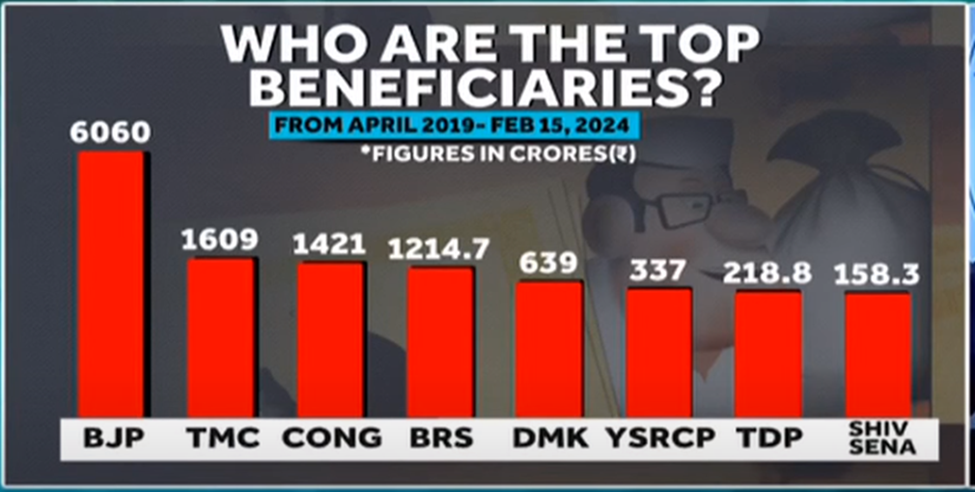

The Modi government introduced the electoral bond scheme in 2017, saying it would make political funding by corporates and individuals a transparent affair. The left parties had vehemently opposed the idea, saying it would legalise corruption by giving the donors a say on the policies and decisions of the government. All the hell broke loose when the Supreme Court of India directed the State Bank of India, which operationalized the scheme, to provide the details of the purchasers and beneficiaries of the schemes between 2019 and 2024. And the tremors have not yet stopped. The information that has been collated till now points to the fact that the scheme was a mammoth machine at work that was used to extort corporates citing their slippages. This, in effect, compromised the interests of the public. It is tough to imagine that the scheme that the BJP said would make political activity more transparent has proved to be working on the opposite direction. Did democracy ask for it?

Worse, the agencies which are formed to investigate major crimes relating to national and financial security have been let loose on the opposition politicians. Hunting down opposition politicians misusing and abusing laws has been a hallmark of the Modi regime, especially during its second edition. The draconian provisions that make bail next to impossible for a person accused under the Prevention of Money Laundering Act, 2002, have been used to the hilt to chase opposition politicians, including chief ministers, and jail them. The principle that one should be presumed to be innocent until proven guilty was made to stand on its head under the Modi regime. The PMLA is was enacted primarily to crack down on drug dealers and their ways of making money; it was a warming that the law will hunt them down and recoup the money they had made through the trade of contraband. Slowly, the ambit of the law was expanded, and no one should have a problem with a politician being held accountable for the black money he amassed through corruption. But instead of doing so, the Enforcement Directorate, the agency empowered to act on the law, has been reduced into a tool to threaten and blackmail opposition politicians. It appears that the government envisages a democracy with no opposition. Does is square with the conventional and constitutional definitions of democracy?

From being a democracy which made every effort to be inclusive, India is in the process of reducing itself to just an electoral democracy with very little participation for the people in the decision-making process. Time that the Indians sat back and thought of ways to emancipate the liberal secular democratic republic that India once was.

(Views are personal)

K.J. Jacob has been a journalist for over about 30 years, having worked with The Mathrubhumi, The Week and Deccan Chronicle.