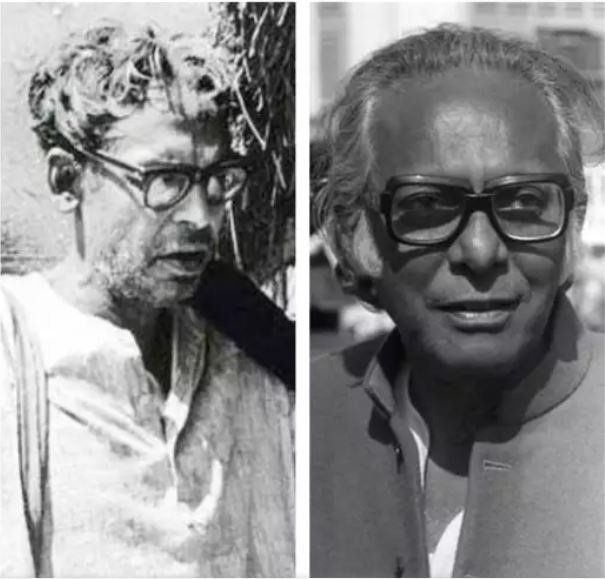

A Comparative Primer on the Films of Mrinal Sen and Ritwik Ghatak

Sandeep Raveendranath [2011 EC]

Mrinal Sen recounts in an interview, his first meeting with Ritwik Ghatak at an Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA) gathering – a lanky young man almost his age was reading out his new play with great passion. IPTA, the cultural arm of the Communist Party of India that nurtured many major literary, artistic and theatrical talents of the age would once again sow the seeds that birthed two giants, in an entirely new medium this time – cinema.

That first encounter turned into the frequent meetings at the Paradise Cafe – a cheap tea-shop in South Calcutta where budding filmmakers – young, unemployed and desperate, gathered to discuss films for hours together. It was during these sessions that Sen decided to become a filmmaker, crediting this momentous decision to both the ambiance of the cafe and the infectious enthusiasm of Ghatak. Today, both Mrinal Sen and Ritwik Ghatak are iconic names in the annals of Indian Cinema – their names etched along with that of another Bengali auteur Satyajit Ray. They were pioneers who changed the course of Indian Cinema, leaving behind the commercial, spectacle and glamour driven movie-making of Bombay in favour of a new kind of filmmaking that treated cinema as the art form that it is, using the medium to focus on social and political issues – the partition, famine, caste and poverty, communalism, the position of women, the anguish of the educated unemployed, dissent and so on. They would go on to inspire filmmakers in other regional languages to walk their path, thereby firmly establishing the culture of the Parallel Cinema of India.

Common Roots

Mrinal Sen and Ritwik Ghatak’s common roots go further back than the meetings at the Paradise Cafe or the IPTA. They were both from villages that became East Pakistan in 1947 (now Bangladesh) and moved to Calcutta during their formative years in an undivided Bengal. These socio-political realities of their time would find its way into their filmmaking – if it was the partition for Ritwik Ghatak, it would be famine for Mrinal Sen. Ghatak’s cinematic world would be a world of exiles where dwell the homeless, the rootless and the child separated from the mother – films peopled with characters who have been driven from their homes, forced to draw sustenance from the vitiated atmosphere of the cities. For Sen, while the physical aspect of famine finds a backdrop in three of his films, it is the ideas associated with famine – poverty, hunger, inequality, and injustice caused by human greed and exploitation that find voice in his narratives. The cinematic medium for Ghatak was the weapon that gave vent to his passionate unrest and for Sen, it was a window through which his keen glance penetrated his surroundings with compassion, humor and sometimes rage.

Early Films

Ritwik Ghatak was the first to reach the milestone of completing a feature film. His first feature, Nagarik (Citizen, 1952) was completed three years before Satyajit Ray’s Pather Panchali but was released only in 1977, a year after Ghatak’s death. Ray once said that, had Nagarik been released before his Pather Panchali, Nagarik would have been accepted as the first film of the alternative form of Bengali cinema. The story of a lower middle-class family which by force of circumstance, finds itself declassed through poverty, Nagarik makes a political statement that remains valid even today – in a city teeming with people, the common man, the citizen, who will never win and yet, refuses to admit defeat. Amidst the squalor and degeneration of city life, Nagarik’s hero emerges with hope. The repeated blows of fortune, the path of despair from the tenement to the slums, cannot kill his spirit – the young, unemployed hero will continue to fight for his right to live. Nagarik was shot on a shoestring budget, with a cast entirely unused to the film medium and skeletal facilities buoyed up on primitive equipment. The technical deficiencies notwithstanding, Nagarik reveals the unmistakable signs of an emerging style and the unique sensibility that permeates Ghatak’s later films. Ghatak even managed to pay tribute to that little cafe that played an unforgettable role in the development of Indian cinema – the tea-shop that the hero visits after his failed job interview is, the Paradise Cafe.

The melodramatic style which Ghatak imbibed during his years as a playwright, actor, and director in IPTA is channeled into his film oeuvre starting with Nagarik. The variety of both indigenous and foreign theatrical styles that IPTA incorporated, such as the Bengali folk form, Jatra, and Brecht’s “epic” form greatly contributed to the theatrical shape of his melodramatic style. Ghatak’s melodrama in the Brechtian sense detached the audience from the action of the narrative; instead of a willingly “suspended disbelief” caused by an emotional investment in the hero’s journey and his fate, the audience was now prompted to produce a critical, objective response to the socio-political commentary that Ghatak was making. The frequent use of wide angle lens, placement of the camera at very high, low and irregular angles, dramatic lighting composition, expressionistic acting style and experimentation with songs and sound effects, carry on through his entire body of work.

Mrinal Sen’s first film Raat Bhore (Dawn at the end of the Night, 1955) meanwhile, turned out to be such a disaster that he once referred to the experience as “that feeling of disgust which envelopes a man after his first visit to a brothel.” His second film Neel Akasher Neechey (Under the Blue Sky, 1959) was laced with subtle political undertones and had a good run at the box office but Sen in retrospect found it unbearably sentimental and technically shoddy. It was with his third film Baishey Sravan (The 22nd Day of Sravan, 1960), that Mrinal Sen really came into his own. An exploration of a personal predicament that grows out of a larger tragedy outside the boundaries of the home, Baishey Sravan, was the story of a middle-aged village hawker and the disintegration of his relationship with his young bride in the context of the Bengal famine of 1943. Sen had witnessed firsthand the ravages of the famine in which he saw people dying in their hundreds on the streets of Calcutta – walking skeletons begging for a mouthful of rice before succumbing to their horrible fates[1]. An estimated 3 to 4 million Bengalis perished in that famine[2] caused by the Second World War and crop failures, and compounded by the callous colonial administration and its racist masters in London.

After the first half of the film is spent on a truly idyllic portrayal of the couple, the famine enters silently. There is not a single shot that represents the famine physically – there are no starving people begging for food, there are no vultures and jackals fighting over carcasses and there are no emaciated babies fiercely sucking the breast of its dead mother. The context of the war and the impending calamity is set up with a shot of a passing convoy, the sounds of an airplane and a very long shot of the villagers moving to the city in search of food. As the cry for food becomes louder and louder outside, Sen keeps his camera fixed indoors where the couple, like two animals in a cage, fight each other as poverty and starvation break down the last vestiges of their humanity.

Ghatak’s second film Ajantrik (The Pathetic Fallacy or The Unmechanical, 1958) had a theme that was startlingly new for Indian cinema at the time – it was among the earliest films in India that showcased an inanimate object – a car, as a major character. The story is about a taxi-driver Bimal and his undying love for his battered old jalopy whom he fondly refers to by a human name, Jagaddhal – a run down, 1920’s Chevrolet that is literally falling apart at the seams. Ghatak humanises the car with a comic treatment – headlights that move of its own volition, and the sense of brotherly affection between Bimal and the car with a number plate that reads “BRO 117”. The dialog Bimal establishes with the car – Jagaddhal never “catches colds” or “gets tummy aches” further highlights the humanising aspect of their attachment. Ghatak’s innovative use of sound design that was way ahead of its time further accentuates this anthropomorphising – while Bimal pours water into the car’s radiator, a gulping sound accompanies the action in the soundtrack. Towards the end of the film, as Jagaddhal is dying in spite of the replacement of its parts and the extensive work done on it, a metallic grinding sound becomes louder and louder indicating Jagaddhal’s “sickness”. While there is still some theatricality, unlike his other films, Ghatak has toned down his use of melodrama in Ajantrik in favor of a comedic-drama form. He still retains some symbolism, for instance in the shot where Jagaddhal is being dragged away by scrap-collectors, the frame is composed through the crosses in the cemetery next to which Bimal lives.

As Ghatak’s concerns over modernism and its discontents are well known, Ajantrik could be read as a cautionary tale about man’s obsession with technology in an increasingly material and urban world. While in an article[3], Ghatak refers to the film as “the story of a crazy man”, and says that “only silly people can identify themselves with a man who believes that that God-forsaken car has life”, the affectionate portrayal of Bimal and his companion in the film certainly does not betray this seemingly condescending tone. In fact, Bimal might well be an extension of Ghatak himself who as an innovative filmmaker, broke all kinds of cinematic rules and regulations. Like Bimal he resisted the fashions of his day, eventually paying the price with an isolation rewarded by a personal vision that goes against the grain. Ajantrik could also have inspired Satyajit Ray to make Abhijaan (The Expedition, 1962) four years later, which had a similar theme of a taxi-driver and his fondness for his car but that film ends on a happier note. This could explain why Abhijaan was one of Ray’s biggest ever successes at the Bengali box-office, while as Ghatak himself recalled, Ajantrik “grossed exactly nothing.”

The Trilogies

After Baishey Sravan, Sen would use the idea of famine again, briefly in Calcutta 71 (1972) and in Akaler Sandhane (In Search of Famine, 1980). All three instances reveal Mrinal Sen as an artist who studied the social and political ferment of his times and informed on them in his art, reincarnating each time with a world of fresh realizations. Calcutta 71 was the second film in his overtly political phase of filmmaking that began with the film Interview (1970). It was a reflection of the violent mood of Calcutta youth at that period of time – the Naxalite movement was at its height and Sen channeled that restlessness into an avant-garde filmmaking that defied the existing Indian cinematic conventions by mixing Brechtian alienation, the cinema verite style, and a non-narrative structure. All the films of this phase – Interview, Calcutta 71, Padatik and Chorus (the first three are known as his Calcutta Trilogy but it could easily be a tetralogy) are characterized by stylistic experimentation where form takes precedence over the dynamism of the thematic entity.

Calcutta 71 was an ideological extension of Interview, both elaborating a Marxist view of class exploitation, poverty, and hunger, resulting in a bitter commentary on the human predicament. Padatik (The Guerilla Fighter, 1973) on the other hand, made a direct political statement by probing those same Marxist values for its contradictions and asserting the need for a timely reassessment. Needless to say, the crowd that sang Mrinal Sen’s praise after Calcutta 71 called him a traitor after Padatik. Padatik was followed by Chorus (1974) which returned to the political philosophy of the earlier two films in the trilogy but was modeled as a satirical re-enactment this time, ending on a note of open revolt.

Padatik is the only film in the Calcutta Trilogy (and Chorus) without a disjunctive narrative structure revealing a distinct beginning, middle, and end. However, this structure is still “interrupted” using the stylistic devices employed in the French New Wave including freeze frames and jump cuts. There are flashbacks and found footage from two foreign films – the Argentinian revolutionary activist film, Hours of the Furnace and Joris Ivens’ documentary on the Vietnam war. There is even an entire sequence where one of the central characters in the film asks several women in a very news-reporting style, questions dealing with women’s empowerment in contemporary Indian society. Many have found these experiments in the Calcutta Trilogy distinctly Godardian and Satyajit Ray was particularly critical calling it an over indulgence in the empty ideological and stylistic posturing of European new wave cinema[4]. While Ray himself has a trilogy on Calcutta (comprising the films Pratidwandi, Seemabaddha and Jana Aranya) that draw comparisons with Mrinal Sen’s trilogy, it is the structural experiments that mark the differences between the two. The question that Jonathan Rosenbaum asks of Luis Bunuel, “how does a sworn enemy of the bourgeois keep his identity while devoting himself to a bourgeois form [narrative cinema] in a bourgeois industry [film industry]?”, is apt for Sen as well. The answer is, “either by subverting these forms or by trying to adjust them to his own purposes.”[5]

Ghatak’s Partition Trilogy – Meghe Dhaka Tara (The Cloud-Capped Star, 1960), Komal Gandhar (The Gandhar Sublime, 1961) and Subarnarekha (The Golden Line, 1962), was the cinematic representation of the socioeconomic implications of the Partition. With these films, he illustrated the mindset of the refugees of Partition by relentlessly drawing the audience into the time and space of those left homeless and crumbling on the faded outskirts of a nation.

Meghe Dhaka Tara was an allegory for the traumatic consequences of the partition of Bengal, capturing the disintegration of a Bengali family as a result of dislocation, poverty, self-interest, and petty internal division. An impoverished family living in a refugee slum after the partition of Bengal struggles for survival and the self-sacrificing protagonist, Nita, has to give up her college studies in order to work. Through many twists and turns of the plot, she becomes the sole earning member of the family. Her elder brother Shankar, who would normally be the head of the household is irresponsible, spending his days singing, dreaming of one day becoming a great singer. He leaves for Bombay soon after, to pursue his singing career returning only at the end of the film. By this time he is an accomplished singer who has become wealthy. However, his ascent to professional and material success has come at the cost of a commensurate decline in Nita’s well being who is now wasting away with a terminal illness.

Striking in Meghe Dhaka Tara is Ghatak’s embrace of the melodramatic style which his background in theatre clearly contributed to. Far from seeing it as pejorative, Ghatak in an article[6] defends melodrama calling it a “much-abused genre,” going on to say in a 1974 interview that “I am not afraid of melodrama, to use melodrama is one’s birthright – it is a form.” The success of Meghe Dhaka Tara, however, is that this melodrama isn’t pure escapism or pure heart-wringing sentimentality but that it exudes a tough, realist sadness – it is his paean to women’s boundless courage and strength, and an indictment of an opportunistic and oppressive social structure.

While Ghatak is known for his eccentric style, his use of the expressionist soundtrack on Meghe Dhaka Tara is certainly bold and experimental. Providing a commentary on the narrative action, Nita’s misery is accompanied by the sound of a whiplash and a hissing sound fades up and down whenever her mother walks into the picture.

In Komal Gandhar, Ghatak merged the motif of fragmentation of a revolutionary cultural movement with a broader motif, the fragmentation of a people. The disintegration of the IPTA and the ideals that it once stood for, had left its mark on Ghatak. The film brought with it an overwhelming nostalgia for the IPTA days where the protagonists struggle to find a new identity in a fast-changing environment as old values crumble. With Subarnarekha, Ghatak provides a prophetic glimpse of the future where post-independence optimism gives way to the harsh realities and disintegrating moral values that are inextricable parts of the civilized urban society. The story of Ishwar and Sita, two of a large, floating population of refugees immediately after independence, it is a bitter tale that mercilessly exposes the canker within.

The archetype of the mother dominates[7] Ghatak’s films and Subarnarekha is no exception with the reconstruction of the Puranic tale of goddess Sati in the character of Sita. In that tale, Sati immolates herself through the fire of her concentration in order to satisfy the ethics of good womanhood because her father Daksha, is greatly opposed to Sati’s husband Shiva whom Daksha believes to be beneath their social status. In Subarnarekha, Ishwar represents Daksha, for he is a surrogate father to Sita and much like Daksha, Ishwar also has an intense dislike for her husband Abhiram because of his lower caste. With the exception of Ajantrik, all Ghatak films from the 1950s and ‘60s show a compulsive engagement with the sister-brother relationship. Thus we have Sita-Ramu of Nagarik, Mini-Kanchan of Bari Theke Paliye, Nita-Shankar of Meghe Dhaka Tara, Anasuya-Pakhi of Komal Gandhar, and Sita-Ishwar of Subarnarekha. As the film critic Moinak Biswas points out[8], “it is consistent with the ‘obsession’ with the mother archetype in [these] films that the brother and sister should form the primary basis of love.”

The music used in Subarnarekha is another critical aspect. Sita sings a Tagore song much like Nita in Meghe Dhaka Tara. The song, which describes the rural Bengal landscape is used to illustrate the innocence and openness of the world of children and to serve as a counterpoint to the degraded and restricted environment of Sita and Ishwar as adults. Another piece of music used in the film – the one in the party scene and Sita’s suicide scene, is the same music from the orgy scene in Fellini’s La Dolce Vita. Ghatak in an essay[9] writes, “There are times when a tune used in a film by someone else is used to make an observation, the way I myself have done. The music that accompanies the scene of orgy at the end of La Dolce Vita, where Fellini lashes out at the whole of Western civilization, is known as Patricia. I sought to make a similar statement in my Subarnarekha about my own land, this Bengal, so sparkling with intellect. So I have used the same music in the bar scene [and in Sita’s suicide scene], to make a suggestion. The music helped me say a lot of things.”

Later Films

Sen returned to the backdrop of famine once again in Akaler Sandhane (In Search of Famine, 1980), this time in the self-introspection phase of his filmmaking. The films starting with Ekdin Pratidin (And Quiet Rolls the Dawn, 1979) to Khandhar (The Ruins, 1983), move away from the anger and bitter satire of his earlier phase to develop an attitude of concern and compassion for the urban middle class of Calcutta bound by their narrow conventions and false moral values. Sen now felt the need to retreat into himself and analyze – “what I used to do before was to locate my enemy outside me. Now I’m trying to find my enemy within myself, to point my accusing finger at myself.”[10]

Akaler Sandhane is a story of confrontations at different levels – between urban and rural culture, between a tragic past and a potentially tragic present, between cinematic illusion and the reality it claims to present, between an artist and his exploitative instincts which he disguises in the garb of creativity. The film is about a film crew going to a remote village of Bengal to make a film on famine. Sen’s humor is evident in this film where at one point, the film crew with its incessant consumption causes a shortage of meat and produce in the village, resulting in a mini-famine there.

The other films in this phase also tackle such contradictions. Kharij (The Case is Closed, 1982), is a subtle understated exposure of bourgeois compromise and the deliberate self-imposed blindness to the reality that makes such a compromise possible. The film uses the death of a child servant as a political symbol, to ponder upon themes of morality and social class, examining the disparity that exists between the lower and middle classes of Calcutta. In the film, a middle-class family employs a young boy as their house servant – a seemingly normal thing to do in Indian homes even today. In a twist of fate, the boy then dies from carbon monoxide poisoning. As far as a plot setup is concerned, this is all that happens in the film. The narrative then turns into a study of how the middle-class society addresses this particular event.

The film opens with a conversation between an unseen couple in the back of a taxicab as the man offers to buy the woman anything she desires – a new apartment, a car, wardrobe, a television set – all invaluable necessities of happy urban living. In the next scene, the woman, visible this time, suggests another commodity – a house servant who can help break coal for the stove, run errands, and be an attendant and playmate to their young son. The attitude of entitlement and commodification is thus foretold in the film’s opening sequence highlighting materialistic privilege as an agent of indifference, discrimination, insularity, and exploitation.

In another particularly revealing sequence that examines the idea of morality, the homeowner asks for advice from a lawyer on the legal implications of the matter. The homeowner claims that the boy had always been treated as a member of the family. His disingenuous words are rebutted by the lawyer who points out that the boy used to sleep under the stairs, was given very little money, and was ultimately regarded as inferior – any positive interaction from the family was minimal, thus making them active participants in the event. The lawyer, however, confesses that ultimately “the legal lie will prevail over the moral truth.” Sen thus exposes a culture of collective accountability, where exploitation of the poor and the weak are rationalized not only by economic necessity but also socially enabled by an implied complicity that reinforces the status quo.

For a narrative that deals with the subject matter of class, and particularly the exploitation of servants, it would be very easy to descend into ideological rhetoric or sentimentalized melodrama. Sen, however, avoids both. He sharply contrasts the dead boy with the privileged and protected son of the homeowner and maintains a pervasive sense of uncertainty – an uncertainty of conflict between social classes, that pushes the story forward.

Without a single line of preaching, the highly nuanced narrative finds the dead boy’s father and another servant boy in the building – representatives of the ‘lower’ class coming through in the end as more dignified than their ‘upper’ class employers.

Khandhar (The Ruins, 1983) explores another guilt and another betrayal – a young man from the city brings along two of his friends, a writer, and a photographer, for a weekend visit to his dilapidated country estate where his cousin Jamini lives, a prisoner of the forgotten past, with her blind and ailing mother. For Subhash, the professional photographer, the encounter with Jamini becomes fraught with the very idea of exploitation and guilt – he takes pictures of her and the sprawling ruins, distancing himself however from any emotional responsibility of participating in Jamini’s painful reality. He returns to the safety of the city, dissociating himself from the experience and relegating Jamini to the one-dimensional prison of a photograph on the wall of his studio. For Mrinal Sen, Subhash is his alter-ego when he says, “I too am intruding with my picture-making machines into the unbearable lives of others, building up a relationship with the young and the old. And then, after finishing the film, I pack up my machines, gather my men and come back to the city, to my tidy, organized room.”[11] Khandhar is then, another exercise in self-introspection, another attempt to understand the foibles of his own time, his own class in the context of a highly personalized cinematic experience.

The memories and nostalgia of his childhood and early youth spent in east Bengal (now Bangladesh) drew Ghatak towards making his penultimate film Titash Ekti Nadir Naam (A River Called Titash, 1973). Based on a Bengali novel of the same title, the film revolves around the life of a fishing community on the banks of the river Titash. The river that gives life to the community steadily dries up, but the protagonist, dying of thirst on its sandy bed dreams of a new life. This assertion of life in the midst of calamity, exploitation, and deprivation is a recurring motif in Ghatak’s films. In Titash Ekti Nadir Naam, it expresses itself throughout the film in the simple joys and sorrows of a people living in daily communion with the river. The song of Lalon Shah, a mendicant poet of the nineteenth century, sets the rhythm of the film which ebbs and flows with the waters of the Titash, investing in the protagonists, the fishing community, a poetic and sentient realism. Ghatak said of the film, “Titash became a kind of commemoration of the past that I left behind long ago. When I was making the film, it occurred to me that nothing of the past survives today, nothing can survive. History is ruthless. It is all lost. Nothing remains.”[12]

The End

While both Ghatak and Sen were participants in the IPTA movement and were both influenced by it, it is Ghatak’s use of melodrama, songs, and coincidence that are telltale signs of his background in theatre. Sen, on the other hand, distanced himself from the sentimentality of his early films, experimented with new wave techniques and settled eventually for a cinema of self-introspection. While Sen made 27 feature films in a career spanning 47 years, Ghatak made 8 features and a handful of unfinished fragments in his film career that spanned 25 years. Sen faced both adulation and intense criticism, especially in the role of a political film-maker. His refusal to stand by an earlier political perception, his eagerness to adapt to his immediate surroundings, his spontaneous response to new political understanding and his constant self-evaluation have all been critiqued from time to time. Yet for Sen, these are signs of growth that he has consistently documented in his work.

Sen recalls his last meeting with Ghatak on Christmas Eve of 1975. While Sen was busy getting ready for the shooting of his film Mrigaya starting the next day, Ghatak arrived at his door unannounced. Emaciated from years of alcohol abuse, with a ghostly pallor on his face and gasping for breath, Ghatak grabbed Sen’s hand like a phantom from the past. The two friends had dinner, they talked and they cracked jokes. Ghatak promised that he would give up drinking. A little more than a month later on 6th February 1976, Ritwik Kumar Ghatak died. In a career ridden with inconsistencies, where extraordinary craftsmanship often went hand in hand with childlike indifference, where the struggle to find money for films met with constant failure, where alcoholism depleted the resources of a keen mind, it is not unnatural that Ghatak found few admirers in his lifetime. Long ago, in his passionate and futile appeal to an indifferent audience, talking about his off-mainstream cinema that had just begun its struggle for survival, he had said, “try to understand that we are moving in the middle of a flowing river. Whatever we are at this moment, that is not our final entity. We shall grow and give shade. We are only waiting for a little sustenance.”[13] Apt then are the last words he ever spoke on the screen, as the protagonist dying in the crossfire between the police and the revolutionaries in his final film Jukti Takko Aar Gappo, “one must do something.”

Sources

- Mukhopadhyay, Deepankar. The Maverick Maestro. New Delhi: Indus, 1995. Print.

- Ghatak, Ritwik K. Cinema and I. Avik Banerjee. Calcutta: Dhyanbindu, 2015. Print.

- Banerjee, Shampa. Profiles: five film-makers from India. New Delhi: National Film Development Corporation, 1985. Print

- Rosenbaum, Jonathan. Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010. Print.

- Mukerjee, Madhusree. Churchill’s Secret War: The British Empire and the Ravaging of India During World War II. New York: Basic Books, 2010. Print.

- Simha, Rakesh K. “Remembering India’s forgotten holocaust.” com. Tehelka, 13 June 2014. Web. 21 March 2017.

- Bingham, Adam, ed. Directory of World Cinema: INDIA. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015. Print.

- Rosenbaum, Jonathan. Movies as Politics. California: University of California Press, 1997. Print.

- Boswas, Moinik. “Her Mother’s Son – Kinship and History in Ritwik Ghatak.” com.au. Rouge (2004). Web. 25 August 2017.

- O’Donnell, Erin. “Woman and homeland in Ritwik Ghatak’s films.” Jump Cut: A Review of Contemporary Media 47 (2004). Web. 21 March 2017.

- Chatterji, Shoma A. “Ek Din Pratidin – Mrinal Sen’s Indictment on Patriarchy.” lcom. Silhouette Magazine, 14 May 2015. Web. 23 March 2017.

[1] Mukerjee, Madhusree. Churchill’s Secret War: The British Empire and the Ravaging of India During World War II. New York: Basic Books, 2010. Print.

[2] Simha, Rakesh K. “Remembering India’s forgotten holocaust.” Tehelka.com. Tehelka, 13 June 2014. Web. 21 March 2017.

[3] Ghatak, Ritwik K. “Some Thoughts About Ajantrik.” Cinema and I. Ed. Avik Banerjee. Calcutta: Dhyanbindu, 2015. Print.

[4] Bingham, Adam, ed. Directory of World Cinema: INDIA. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015. Print.

[5] Rosenbaum, Jonathan. Movies as Politics. California: University of California Press, 1997. Print.

[6] Ghatak, Ritwik K. “Film and I.” Montage Vol. 2, No. 3 (1963). Print.

[7] Ghatak, Ritwik K. “Face to Face.” Cinema and I. Ed. Avik Banerjee. Calcutta: Dhyanbindu, 2015. 216-17. Print.

[8] Biswas, Moinak. “Her Mother’s Son – Kinship and History in Ritwik Ghatak.” rouge.com.au. Rouge (2004). Web. 25 August 2017.

[9] Ghatak, Ritwik K. “Sound in Cinema.” Cinema and I. Ed. Avik Banerjee. Calcutta: Dhyanbindu, 2015. Print.

[10] Chatterji, Shoma A. “Ek Din Pratidin – Mrinal Sen’s Indictment on Patriarchy.” learningandcreativity.com. Silhouette Magazine, 14 May 2015. Web. 23 March 2017.

[11] Banerjee, Shampa. Profiles: five film-makers from India. New Delhi: National Film Development Corporation, 1985. Print

[12] Ghatak, Ritwik. “Director’s Comments on Titash Ekti Nadir Naam”. Cinema and I. Ed. Avik Banerjee. Calcutta: Dhyanbindu, 2015. Print.

[13] Ghatak, Ritwik. “Rows and Rows of Fences”. Cinema and I. Ed. Avik Banerjee. Calcutta: Dhyanbindu, 2015. Print.